What’s this all about then?

Fruitbat (that’s us – Tim Mannveille and Clare Huxley) ran a game called You’re In A Room at the recent(ish) first of Hide & Seek’s “Games with Audiences” Sandpit series, on Friday 25th May.

We’re particularly pleased with how it turned out, since it involved players creating challenges for each other (uh-oh…) but the nature of the format meant that players pretty much always completed those challenges by the skin of their teeth! (Hooray!)

This is the story of how that came about!

And why do you need me?

The game involves a small team guiding one blind-folded player through a virtual dungeon, with that player generally asking a bunch of questions. We’re having form reflect content by you playing that role.

Where am I?

You’re In A Room! This was the repeated-and-therefore-magical phrase that was invoked whenever a player advanced in the late 80s/early 90s kid’s TV show Knightmare, in which a player in a bucket-like sight-blocking helmet was blue-screen-comped into a matt-painted / CG dungeon populated with actors, props, and virtual peril, there to be guided by their team-mates watching over them through a television, thereby creating a game perfectly designed to make you want to shout at the screen. You can get an idea of the show very quickly by watching this clip:

So where does your version fit in?

One day at work, Tim discovered a desk-side bin hidden inside another desk-side bin, with a piece of paper taped to it featuring an upside-down face and the word ‘Friday’:

On hearing this, Clare was reminded of an impulse from long ago to make some kind of “bucket head” game, using the sighted-players-guide-player-with-bucket-on-head device so familiar from Knightmare.

A few days later, Hide & Seek announced the dates of their summer 2012 sandpits, starting with one themed around “Sports and Game Shows,” and even though this was only four weeks away and all we really had as an idea was “Bucket Head”, we figured this was the perfect opportunity to do it.

“To achieve great things, two things are needed; a plan, and not quite enough time.”

– Leonard Bernstein

Clearly, we didn’t quite have enough time. So all we needed now was a plan.

What’s in this room I’m in anyway?

What? Er, a computer. Anyway, the plan was to very quickly come up with a workable idea, playtest it once, tweak it, and run it.

After quickly veering away from an ambitious idea involving multiple simultaneous players guided by walkie-talkies (which we may may well come back to), we were ultimately drawn to a more literal idea of creating a kind of mini, Sweded version of Knightmare, the hope being that some of the back-seat-player audience involvement engendered by the original show would carry across.

Clare suggested one key twist: that the players should have the opportunity to come up with dungeons themselves, thereby solving the problem that the original Knightmare had more people running the game than actually playing it. But could it work?

We distilled what we thought were the key elements from Knightmare (a character, a puzzle, a reward, a physical challenge, an obstacle that could only be passed with the right item or spell), created three-room templates, rustled up some friends, and just gave it a go.

So did it work?

The optimistic vision was that a game might take 5 minutes, and Tim in particular was drawn to the idea of a constantly rolling drop-in format in which one could rapidly move up a sort of engagement ladder:

From passive audience member, to…

> Back-seat-player

> Player

> Dungeon designer

> Dungeon operator.

The test very quickly revealed a problem with this idea: people naturally tended to design complex dungeons that took more like 15-30 minutes to play, and some of their rooms would take longer to set up than to play – not ideal.

On the positive side, it had one particularly outstanding feature: dungeon-designers wanted the players to experience everything they had made, so when playing the part of monsters/hazards/obstacles, they would tend to tweak things on the fly such that a player would succeed – but only just. This is great, because we’ve seen before that the moments that players enjoy the most are those in which they feel they succeeded by the narrowest of margins. We had stumbled upon a game format that pretty much generates these moments by default. Wow!

So how did you tweak it? And does this computer have internet access?

Er, yes it does. First we revised the instructions (and briefing) so that, with some guidance from us, a team could hopefully invent a dungeon in 15 minutes that would itself take 15 minutes to play.

Second, we had another look at the logistics, and were drawn to the idea of a structured rolling format with two tracks of players – dungeon-designers, and dungeon-players – hoping that this would create exactly the opportunity for progressive involvement (from audience member on upwards) mentioned at the start.

Finally, we realised that riddles were a fun feature of the genre, but it was tough to come up with them on demand, so we prepared a random selection that players could draw from if they got stuck.

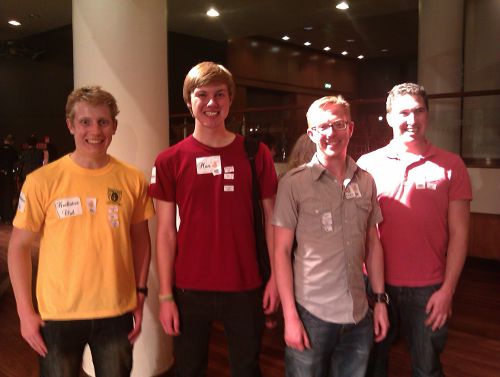

On liaising with Hide & Seek, we were advised that this 15-minute version probably wouldn’t schedule well with other games (which tend to have defined 30-to-45-minute slots); a better format would be to have defined 1-hour slots in which 3 teams could first design their dungeons, then rotate through the roles of audience/dungeon-operators/players over three 15-minute slots. Although this removed the possibility of allowing spectators to become players and then performers, it seemed the most practical way to try the game out in this context – and in particular, to see if we really could have people stick to that 15-minute time limit.

What happened?

What happened was this: for the first group of players, we actively pushed to have dungeons designed and run as quickly as possible – and ended up finishing the hour slot with just under 10 minutes to spare. We let things follow a more natural pace for the remaining two hour-long slots, and amazingly they worked just about perfectly.

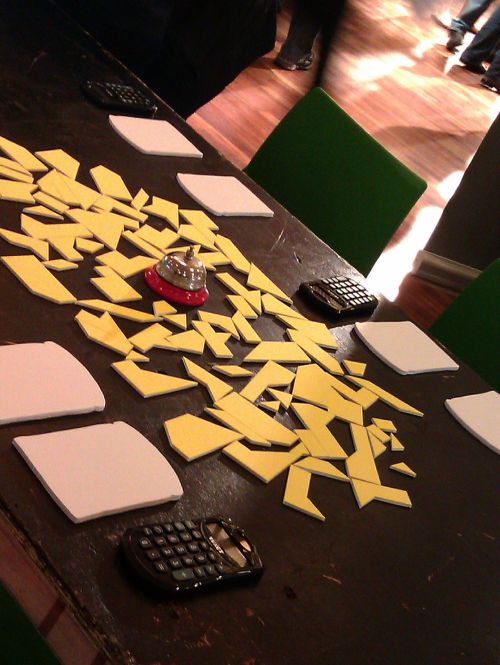

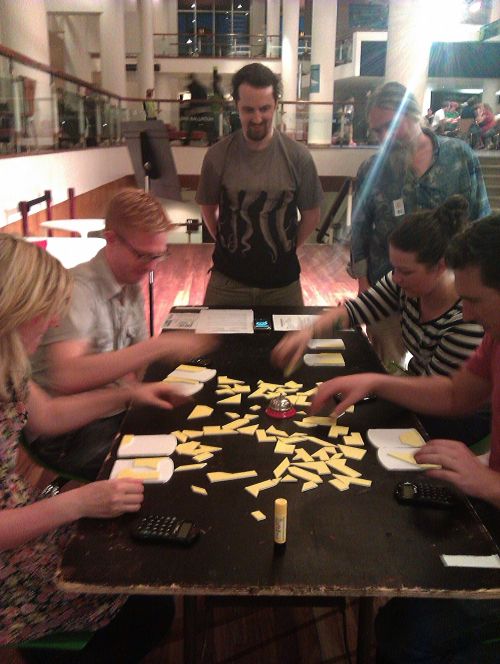

The other nice feature was that in the absence of specific theming, people came up with a huge range of dungeon types. Here’s a quick overview of what was produced:

7pm-8pm, Team A: North Korea Dungeon. Great use of one of our hat props for that authentic single-party-state feel.

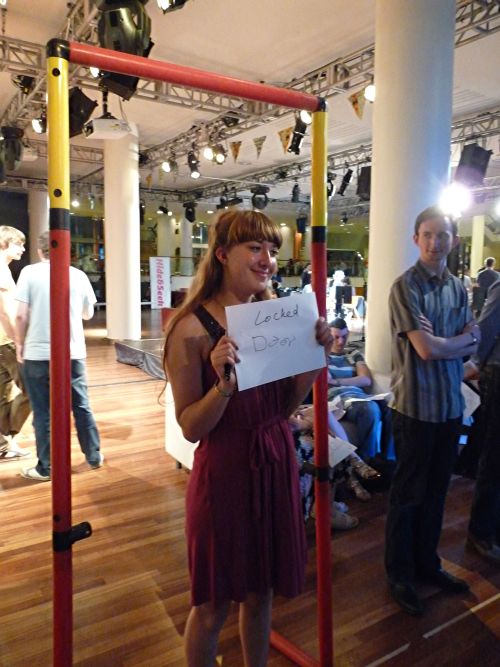

7pm-8pm, Team B: Fun House Dungeon (a kids gameshow from the same era and channel as Knightmare). We particularly liked the use of the whiteboards as story-board-like captions, for example, the guy playing Pat Sharp holding a sign that says “PAT SHARP APPEARS” as he appears:

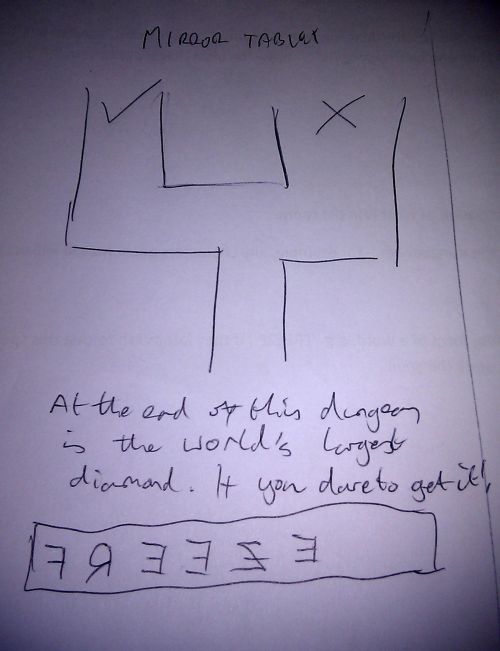

7pm-8pm, Team C: The Mirror Dungeon. The players find a map with mirror writing showing that the left exit from the room is deadly. Which way do they go?

8pm-9pm, Team A: A somewhat adult-themed dungeon we later realised was probably called the Knightclub dungeon. Notable for use of the spell ‘B-E-E-R-G-O-G-G-L-E-S’.

8pm-9pm, Team B: The Jelly Dungeon, featuring an extra challenging variant on the form: with the entire dungeon made of jelly, the blindfolded player could only ever stand on one leg. Tricky, but as it turns out, doable – hooray!

8pm-9pm, Team C: The Classical Dungeon, in which a player had to play ‘Stairway to Heaven’ on a paper flute to put Cerberus to sleep. Most notable for this exchange:

One of Cerebus’s heads: That’s not how it goes at all!

Player: I’m doing the intro!

9pm-10pm, Team A: Robot Science dungeon. An amazing use of the form in which the player first discovers that they are actually a robot, before solving the final room by discovering the human within themselves. Not bad for 15 minutes.

9pm-10pm, Team B: The Not-At-All-Based-On-Indiana-Jones Dungeon, most memorable for the entire dungeon-operating team stamping their feet just behind the player to simulate the approach of a giant boulder.

9pm-10pm, Team C: The Pirate Dungeon, featuring some great pirate acting and buried treasure recovered seconds before the Sandpit event came to an end. Hooray!

I write a blog post about You’re In A Room. So what would you change for next time?

A lot depends on the setting. If the venue was suitable, we’d love to try some version in which the game is ‘rolling’ – probably with some volunteers on hand to do the dungeon-operating part by default, but who could step aside if people want to come up with a dungeon themselves. This means players get to see how the game works before designing a dungeon (a major challenge in this first run of the game), and also brings back the possibility of bystanders graduating from back-seat players to actual players.

Another setting-dependent issue is the noise level. With two other games making use of amplified sound nearby, and the general hubbub, it was tough for the dungeoneers to hear their directions. As a quick fix, teams simply stepped into the room themselves, which made things a bit surreal, but did work. Unfortunately, this also meant that any bystanders / audience members would struggle to follow what was happening unless they too got right up close to the action. In a similar situation, some kind of amplification may be called for.

The most important change would be to further distill the instructions. The set we used worked – players were indeed able to come up with suitable dungeons within the time limit – but they did look quite intimidating. If players also get to see a dungeon in action first, this also becomes much easier.

Finally, we’re also thinking about adding more hats, because hats are where it all began, and because everyone loves hats.

Okay, I publish the post.

-Tim & Clare, now known as Octopus Fruitbat

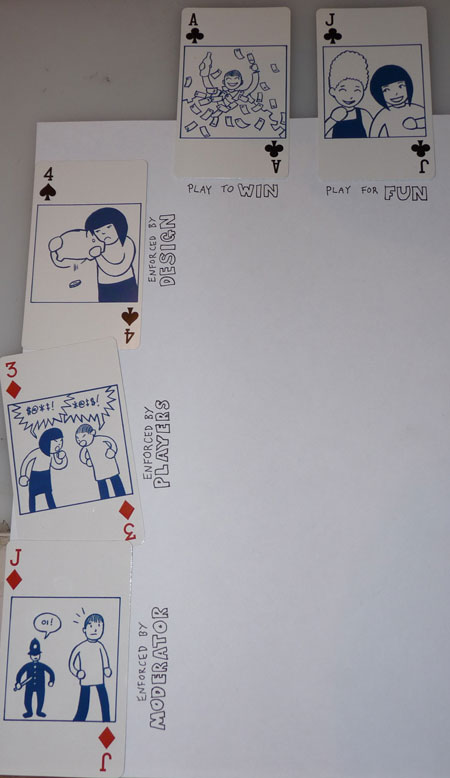

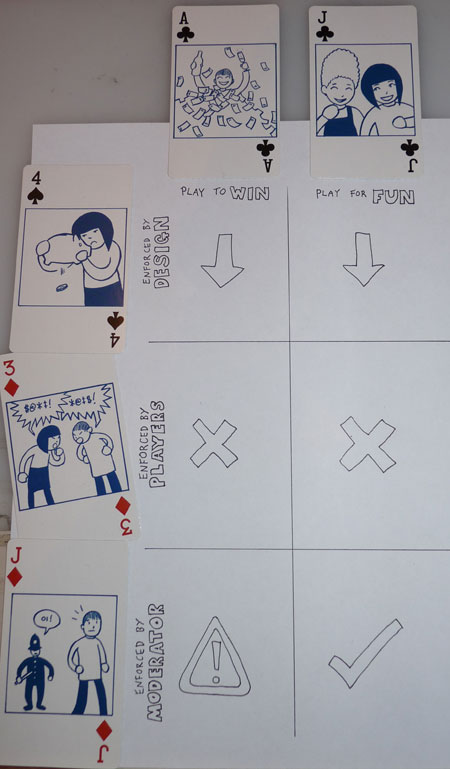

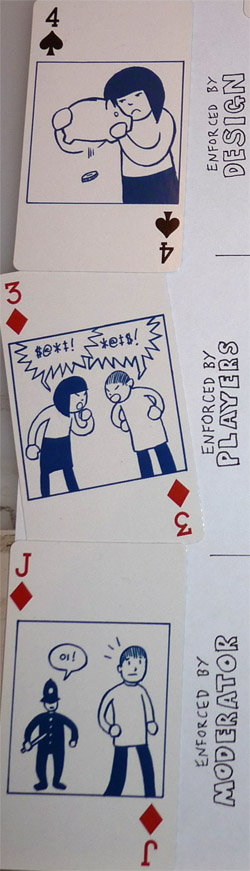

Let’s take a look at how cheating works across the 6 kinds of game this framework implies, and in particular whether choosing to bend or break rules is an interesting* choice for the players to make.

Let’s take a look at how cheating works across the 6 kinds of game this framework implies, and in particular whether choosing to bend or break rules is an interesting* choice for the players to make.