Q: What’s the difference between Star Wars fans and Star Trek fans?

A: Star Trek fans don’t hate 90% of their movies!

As a life-long Star Wars fan, this joke resonated with me: my position of finding a lot to enjoy in literally every Star Wars film now seems highly unusual. It also raises an interesting question. What does it mean to be a fan of something you are mostly angry about? How does that happen?

I’ve been thinking about this for a few years now.

Here’s what I’ve figured out.

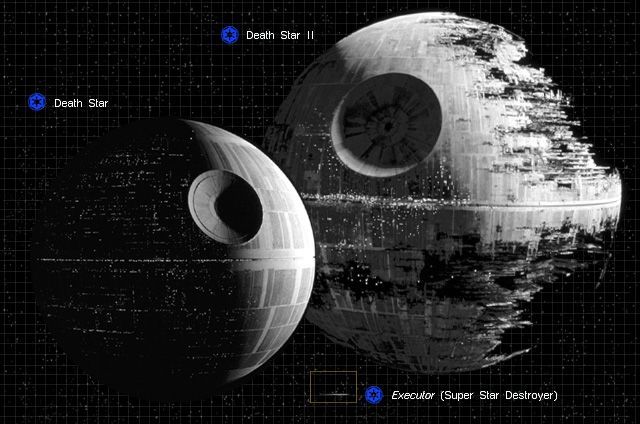

That’s No Moon

This phenomenon is much bigger than Star Wars, if such a thing is possible.

As an area of work and personal curiosity, free-to-play mobile games show a particularly stark example of what I’m calling ‘Paradoxic Fandom’. Studying the games that have found greatest long-term financial success, I noticed that almost all their player communities tended to have the same repeating refrains:

- Every update makes the game worse

- The game is dying

- The developers are out of touch with players

- The developers only care about ‘x’ players (x is either new players, or the biggest spenders)

Where I work, it was particularly noticeable that we didn’t get much feedback like that until we came up with our first truly successful long-term game.

I’ve seen Paradoxic Fandom elsewhere too.

- The dominant feedback on most social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter etc) is that all changes to that platform are for the worse… but people keep using them.

- The ‘Bad webcomics wiki’ seems like the go-to place for fans of a webcomic to complain about how much they hate it.

- In Future Shock (2014), a documentary about the long-running UK anthology comic 2000AD, one of the historic editors draws a distinction between ‘readers’ and ‘fans’; he implies that the fans were the most difficult to deal with.

- I keep in touch with developments in LEGO through the blog From Bricks To Bothans; it became apparent that main writer Ace Kim (since 2002!) has a similar love-hate relationship with LEGO (sample: a review of the ‘Ultimate Collector Series’ LEGO Star Destroyer, ending with “Things like this re-affirms my decision to stop collecting LEGO”)

It’s not just statistical regression

There’s two phenomena that look a bit like what I’m talking about, but are meaningfully different: the Sophomore Slump, and its close relative the Sports Illustrated cover jinx.

The Sophomore Slump occurs if someone (or a group of people) perform worse when they have less to prove. Having found success on their initial effort, they may try less hard for the follow-up, be it students in their sophomore year, or bands on their second album.

The Sports Illustrated cover jinx is when an athlete performs exceptionally well, gets featured on the cover of the magazine, then has a disappointing performance immediately after. It’s possible that some athletes find the additional scrutiny difficult to deal with, but this seems much more likely to be a simple case of regression to the mean: in anything where there’s a fairly strong random component to performance, an outlier is most often followed by a more average result.

This can apply to almost anything. For example, I found out the excellent line “I’ve come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass… and I’m all out of bubblegum” was from the film They Live (1988), but when I eventually watched it, literally nothing in it was as good as that line. Regression to the mean!

But Paradoxic Fandom is an ongoing, sustained effect, so it’s not just a statistical regression/slump/jinx.

Paradoxic, not yet toxic

When consumers begin to harass or threaten people they perceive as damaging the thing they love, they have crossed a line into what gets termed ‘Toxic Fandom’. Here, I’m interested in the wider phenomenon, which can easily give rise to Toxic Fandom but is meaningfully distinct. So I’m calling it Paradoxic Fandom, and the key defining features are:

- The product/service is ongoing over months, years or even decades

- Fans continue to consume and engage with the product

- … but they report finding the product/service consistently disappointing, getting worse over time

- … and they believe this is because the creators are out of touch with the fans

So what is going on here?

I think this actually begs four related questions:

1) Why do companies do things badly?

Why can’t video games harness everything they learned and get better with every iteration? Why, when there is clearly money to be made in satisfying a large audience, does capitalism fail to deliver?

2) Why do consumers misjudge things?

If criticism is unwarranted or short-sighted, why does that happen?

3) Why do people remain fans/consumers of things they seemingly hate?

4) Even when responses are mixed, why does criticism dominate the discourse?

I’ve been thinking about this ever since the borderline-allergic reaction of some ‘fans’ to The Last Jedi (2017). Here’s what I think is behind each of those questions.

1. Why do companies do things badly

What about the money?

If something is a financial success, the budget for follow-ups is likely to be bigger, which in theory should help. But while money helps with execution, in artistic endeavours it’s very clear that money cannot buy ‘quality’ (whatever that is) – if it could, movie and game studios wouldn’t lose the most money on the big-budget failures, but that’s exactly what happens.

You can’t please all of the people all of the time

The follow-up thing will certainly have similarities to the original thing, but also differences; the people who loved the first thing will have liked different things about it, so inevitably some will be disappointed.

More money, more problems

Companies generally try to make more money – like LEGO looking to grow their business, or a free-to-play game looking to maximise profits. Much as capitalism is built on the lucky fact that in the right environment, competitive self-interest can produce great results for everyone, the end-result is always some kind of compromise between buyer and seller.

One simple factor is that a company will try to make more money out of their customers. Most benevolently this could be by making further content, but there are less benevolent ways too (most simply, releasing a DVD with two different slip-cases to try to get fans to buy two copies).

But that can only go so far. Generally, the best and most scalable way to make more money is to find more customers. It’s quite possible that having attracted all the customers you can with your existing product, you’ll need to make some changes to attract larger numbers, which brings us back to not being able to please all the people all of the time.

2. Why do consumers misjudge things?

I should make one thing very clear: when people complain about things, it is often worth listening, and very productive action can be taken as a result. But sometimes, as consumers, we do misjudge things, and that criticism is less useful. Why does that happen?

One thing I’ve found is that making things – really, almost anything – is always more difficult than you expect.

I see a connection between the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect (read a newspaper article about something you know and see how wrong it is; go on to assume everything else you read is just fine) and the Dunning-Kruger effect (non-experts have a sense of illusory superiority, because they don’t know enough to know better).

In whatever area you work or have expertise, you should be able to identify how wrong most people are about it. Most obviously I find this in any question that begins with “Why don’t they just…?”

A personal example: I want a new mobile phone, and battery life is much more important to me than weight or how thin it is – but I can’t find such a phone on the market. Why don’t they just make a version of a great phone that’s much thicker in order to have a bigger battery?

But if I try to imagine the sorts of things I’d know if I designed phones, I can imagine that there might be complicated cooling issues with a thick battery; or perhaps they make trial-concept versions of potential new designs and have people use them for a few weeks, and discover that even if you think you’d be okay with the weight/thickness trade-off, it’s ultimately too annoying. I can even more easily imagine there’s a reason that I can’t conceive of at all!

Knowing the answer to these questions about one’s own areas of expertise, one should really extend it to other areas. When you start to ask “Why don’t they just…” you should remember Gell-Mann’s newspaper experience and the Dunning-Kruger effect, and consider if perhaps you just don’t have the expertise to spot the problems with your idea.

Another example, from an area of personal expertise: in anything involving code, new updates bring new bugs. The frequent response is “Why don’t they just test it properly, and make sure all the bugs are fixed before they put out the update”. The problem with this is that, on average, it takes longer to find each incremental bug than the last (things that occur one time in ten take longer to find than those that go wrong every time; things that only happen under very particular circumstances only turn up if you test extremely large combinations of actions, etc). As such, to truly guarantee all bugs are fixed would take so long that the customer waiting for their bug-free update will have moved on long it arrives. In the real world, ‘the perfect is the enemy of the good’, and compromises have to be made to get anything done.

Follow ups like “Why don’t they just hire more/better testers”, “Why don’t they let players/customers test it first” run aground in a very similar way. (Don’t forget though, there might actually be reasonable ways to improve things a bit! Customers are great at identifying problems, but it’s on you to figure out the solutions).

So we see why professional efforts aren’t improved as simply as consumers often assume . I think there are four other reasons consumers can be disappointed by updates: expectation failures, familiarity contempt, confirmation bias, and in the longer term, simply ageing. Here’s how those break down:

Expectation failure

A combination of factors tend to make us inordinately sensitive to our expectations not being met. For example, I use the internet on my train commute, and one time the train went into a tunnel, so the internet cut off, and I immediately felt annoyed. I realised this was a ridiculous response: I’ve made the journey hundreds of times, I’ve literally made a spreadsheet to identify where in the journey internet access drops. But in that brief moment, my expectation of continued internet access failed, and therefore in that moment I was annoyed.

In creative media this seems most obvious in movies, where the most significant factor in how much someone enjoyed a film seems to lie less in its objective qualities but more in how it compared to their expectations.

As noted above, a follow-up thing must be at least a little different to the original thing. Expectations are based on the original thing, so some expectations can’t be met – so some disappointment is inevitable.

Familiarity Contempt

‘Familiarity breeds contempt’ sums this aspect up well.

The IMDb ‘goofs’ section for 1977’s Star Wars Episode 4 is one of the longest of any film. But this is not because it was a terribly made film. It’s because so many people love it so much, it has received orders of magnitude more scrutiny than most other films.

I think this applies to the LEGO example, and especially to successful mobile games. These superfans are so close to the material they see every flaw. Something that seems perfectly functional to a casual player could be perceived by the superfan as being riddled with bugs.

So this is another effect: the people that engage the most with a thing will also be the most knowledgeable about its flaws.

Confirmation bias and performative criticism

Reality is complex and nuanced, so I think we make it more digestible by applying confirmation bias. If there’s something/someone we think is good, we are more likely to overlook or discount their flaws; if we judge something to be bad, every fresh piece of evidence is another chance to spot something wrong with it. It takes active, conscious effort to try to maintain a balanced view.

As a thought experiment, when was the last time you changed your mind about something? I find this to be alarmingly rare in myself. How likely is it that my immediate judgement of something was wrong and should have been corrected, once further evidence emerged? If I’m very optimistic, maybe not that often – but certainly much more than actually seems to happen.

I think this applies to many artistic endeavours. If for any reason your judgement on the creator of something has soured, you are likely to apply confirmation bias to their subsequent works and seek out their flaws to confirm your belief.

With art taking many forms, this produces an interesting corollary: the sooner you experience a follow-up work to something, the more likely you are to apply confirmation bias and continue to enjoy it – or hate it. If you are enjoying a TV series, I think a new episode is more likely to benefit from positive confirmation bias than a new series, which in turn is much more likely to maintain positive bias than a revival of the series many years or decades later.

Let the hate flow through you!

Related to this, I noticed that many criticisms of The Last Jedi in particular were bad-faith interpretations of plot, applying a level of scrutiny no screenplay could survive – an example of negative confirmation bias. It seems as if there are incentives to enact a kind of performative criticism once you flip into negative confirmation bias. So as an experiment, I wondered what it would be like to apply this to that sacred text, Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (as it was called in the re-release; just ‘Star Wars’ in the original release, which is the one post-release change that interestingly escapes criticism).

Please put on your flame-proof goggles and hold your nose as I have at it.

There’s so much wrong with this film it’s hard to know where to start, but let’s just go from the beginning.

Darth Vader is a terrible villain and an idiot. His “big entrance” is to come in after a bunch of cannon fodder have already done all the fighting, and then he does some kind of useless interrogation on someone that’s already been subdued. More importantly, he’s chased this ship to Tatooine, where the rebels presumably have a contact, and when the Death Star plans are obviously sent down to the planet in an escape ship, what does he do, as the guy with the ability to sense things with the Force? Just send down a bunch of useless stormtroopers to walk around asking if anyone has seen any droids lately?! What exactly is Vader doing while that’s going on – did he have to leave in a hurry to get to the big exposition meeting in the Death Star?!

And then later on, the Falcon, the very ship that escaped Tatooine – obviously with the plans – gets caught by the Death Star; Vader is right there standing in front of it, he senses ‘something’… and then walks off?! Oh it’s fine, we’ll just send in the guys with the scanning machine instead! But wait, what’s with this scanning machine you have to physically take into a ship to operate? At the start when the droids take the escape pod, the Imperials scan it remotely for life forms, so why can’t they do that in the Death Star?

Okay, how about the heroes. Well, Luke is the most pathetic magical orphan character ever conceived. There’s literally nothing likeable about him. All we know is he apparently wants to get off the planet to… join the academy (what, the Imperial academy? What kind of ideal is this?!), but all he does is slouch around and whine about his chores. His step-parents are then apparently roasted alive (weird tonal imbalance, BTW) and he’s sad for about two seconds. People talk about how he’s a great pilot, but the first time we see him in a vehicle he’s in a land speeder keeping an eye on the scanner – while C-3P0 drives?! Whatever happened to “Show, don’t tell”?

Oh, but he’s magic! Obi-Wan teaches him to ‘stretch out with his feelings’ and suddenly he can hit a target no computer can hit, in a spaceship he’s never flown before! And also, by the way, despite never having fired a gun, he’s actually a crack shot, able to shoot out door controls from across a room, and out-shoot trained soldiers in multiple encounters! Also: he’s given an incredible weapon in the form of a light sabre… and then literally never uses it. Has Lucas never heard of Chekhov’s Gun? Why didn’t Luke use his light sabre to escape the trash compactor?

Oh, but the film has such a great back-story, right? Obi-Wan Kenobi has been apparently waiting for Luke to grow up so he can give him his father’s light sabre, and train him in the force. But, er, what was he waiting for exactly? Could have started a little earlier maybe? If Darth Vader had actually come down to sort things out Luke would have been killed before they even met! As it is, Obi-Wan literally gets in about 2 minutes of training before dying! (Another tragic death which Luke shrugs off in less than a minute, before running off to man the ship’s gun-turrets, which, by the way, is yet another thing he’s never done before that he’s apparently great at).

Alright, how about the Death Star. This whole thing is one giant plot hole. So apparently you can fly around the galaxy at faster-than-light speed in a station the size of a small moon? Why even build a hugely expensive space station then? Just stick a light-speed engine on a moon and fly it straight into any planet you don’t like! Oh, but I guess if that’s possible maybe the planet could just fly out of the way with their own giant engine!?

And how about that Death Star security? Literally any random droid can unlock doors and operate machinery from any random access port? Except tractor beams, which can only be disabled from a lever on a vertiginous ledge for some reason? And doing any of this doesn’t notify anyone anywhere apparently? And there’s so little CCTV that a bunch of random idiots can run around and you don’t even know where they are? They literally escape a dead end by jumping through a waste pipe and nobody can figure out to just throw a grenade down there?!

So probably the most sensible character is Princess Leia. She spends the whole time being rude to everyone she meets, but she’s at least smart enough to figure out they are being tracked when they leave the Death Star – but what does she do about it? Try to find and remove the tracker, or maybe go to another system and switch ships? No, let’s just go straight to home base, it’s fine, we’ll have at least half an hour for our techs to figure out a weakness in this giant planet-destroying space station that can be exploited by, er, about 30 small ships! I’m sure we can do that before it blows us all up. Wow! Good thing the plot wants this to succeed or this rebellion would be over!

And then finally, the big climax: the trench run. First, what even is this trench? And the secret weakness – literally one torpedo in the wrong place on the outside of the station blows the whole thing up? What kind of design is this exactly?

Given this lucky gift, what do the rebels do? Take it in turns to fly really far away from the exhaust port, and then spend ages flying along this trench to reach it, so the enemy can take them out one by one?! If you have the element of surprise, why not go straight to the exhaust port? Or why not all go at once? And even if there was some reason for the long run-up, the day is apparent saved when the Millennium Falcon comes in at the last second and shoots the bad guys at the end of the trench – er, literally any of the other X-Wings could have done that on any of the previous runs?

And…. breathe.

So, what just happened there? Wasn’t that far too long? Why yes, yes it was. Writing it was easy, fun, and made me feel smart, so I wanted to keep going. I can actually now understand why someone might read/write things like this over a prolonged period of time, rather than positively engaging with something they enjoyed. If it seems hard to imagine, I recommend giving it a go with something you know well yourself!

(Edit: I’ve seen cases of people reading this post and then arguing against the points raised in the screed above. This is the opposite of the point! Almost none of those arguments ever occurred to me before – I only thought of them when I considered the film specifically with an intent to pick it apart. I could argue strongly against them myself! Rather, the point is instead to consider a film you love, and then try to find the problems with it. Going through this exercise was very revealing for me as I noted above. It’s also interesting to examine how you’d argue against your criticisms; if you find yourself extrapolating beyond what is explicitly shown in the film (eg. the mechanics of different life-form scanners), or drawing on other material not in the film itself (e.g. Anakin’s history with Tatooine), do consider that these approaches could also benefit films/games/whatever that you are less inclined to extend the benefit of the doubt – T.M. 13th Jan 2022).

It’s not them, it’s you: fandom vs. ageing

On a time scale of multiple years or even decades, a newly significant effect enters: the viewer/consumer/player themselves has significantly changed. I suspect this is where Star Wars suffers the most. The main saga films are (I think) most enjoyed by children; when a new trilogy comes out 16 years after the last, those children have grown up!

I remember many Star Wars fans who were disappointed by the prequel trilogy nonetheless really enjoying the 2003 animated TV series. This had a lot of over-the-top action that would never stand scrutiny in live-action form, but I suspect the animated format bypasses a lot of the adult reality-check apparatus, and allowed these folk to be childishly delighted in the way they originally were.

This became particularly evident with Disney’s more recent Star Wars sequel trilogy. I’ve seen many young fans citing the prequel-trilogy as a superior era (echoing – yet reversing – the response to the prequels at the time, when they were reviled by fans of the original trilogy). This is also evident from the comments endorsing the Scene 38 Reimagined video – a fan video replacing the somewhat feeble 1977 Obi-Wan vs Vader lightsaber battle with something more like the prequel or sequel trilogies (and which would be utterly out of place in Episode 4).

So there are many reasons that account for strong criticism from fans, but don’t get the wrong idea: that should never be taken as an excuse to disregard all criticism! Criticism from consumers is often valid and useful for companies to heed (especially that familiarity/mistakes one) – you just have to take these effects into account.

3. Why do people remain fans of things they seemingly hate?

So, companies disappoint people because money can’t buy quality in artistic areas; and also because you can’t please all the people all of the time but companies want to continue and grow. Fans will be disappointed by new works due to expectation failure, confirmation bias (earlier disappointment drives fresh disappointment), familiarity contempt, and ageing; their analysis of the flaws may well be completely valid and useful feedback, or may be flawed due to the Dunning-Kruger effect.

The obvious conclusion is that people would simply stop consuming things they hate and find something new. But evidently, in many cases, that doesn’t happen. Why?

First, I think it’s a clue that everything affected by Paradoxic Fandom is in the arts or services; products don’t seem to have the same issue.

My friend John Broughton referred me to the 1970 book “Exit, Voice and Loyalty” by Albert Hirschman. To paraphrase significantly, “exit” means a customer stops using the service, and “voice” is what happens when “exit” is not possible: the customer voices their feedback on what they don’t like in the hope it will improve. I think this explains why products get off the hook – exit is fairly easy, you just buy something else.

In creative products, there is no easy exit. If you don’t like the sequel to a game or film you love, there is no alternative version you can switch to. In services, switching is either impossible (you can’t take everyone you interact with on a social network with you) or has a high enough cost that it’s better to stay. In the games-as-a-service model, it’s amplified further: when an online game updates, there’s no way to carry on playing the old version you liked better. To keep playing you have to accept the changes.

A fascinating exception that proves the rule: Runescape found a way to work around this. They released ‘Old School’ Runescape, recreating the older version that most fans first fell in love with – while continuing to develop the newer version. They now continue to develop the ‘Old School’ version, but all changes in it must pass a majority vote by the players.

So if you love a thing, and it changes in a way you don’t like, and you can’t switch… well of course you’ll be vocal about it! This is perfectly reasonable!

However, as “Why don’t they just…” is almost always unfounded, and as cultural products must appeal to more than just one person, very often that feedback won’t (or even can’t) be heeded. At this point, things can get pretty rancorous.

4. Why does criticism dominate the discourse?

From Paradoxic Fandom to Toxic Fandom

SamSykesSwears summed up the stages of toxic fandom (I think referencing the pattern of abusive relationships) in this tweet:

- I love this

- I own this

- I can control this

- I can’t control this

- I hate this

- I must destroy this

For example, the changes George Lucas has made with each edition of the original Star Wars trilogy particularly provoke “I can’t control this”. The clue to the irrationality here is how in many reviews, literally every single change is reviled. It seems improbable that literally every change the original creator would make to their creation before it came out was good, and every one after is bad. This looks far more like a near-religious adherence to some sort of holy text.

I think this was insightfully extended in a response from EricVBailey:

- I can’t destroy this

- I am even more mad now

- I can harass those who are part of it though

- I found a whole community of people doing this

- I have found my validation

- I love this

Self-selection and feedback loops

Even given all the above, it seems odd that a casual glance at much online discourse tends towards negativity, and especially the more toxic end of it. I think two things are at work here.

One is self-selection. This is easily seen in Amazon reviews of products: the majority of reviews seem to be people who only just got it (so have nothing useful to add), or who have had some terrible problem. This is because both of those moments are cues to leave a review. Using something and having it work just fine does not prompt you to go write a review. Similarly, playing a mobile game or watching a movie and simply enjoying it does not motivate you to review / talk about it online as much as hating it does.

So self-selection skews what people tend to write about things.

The other factor is Feedback loops.

There are a few feedback loops online that end up fomenting more toxic discourse. One that has been well-covered (I thought particularly well by Tom Scott’s Royal Institution lecture) is that algorithms optimising for people to spend time on a platform will tend to find success by showing people more extreme and click-provoking content, which is often negative. So YouTube will naturally take you from “10 Things You Missed In The Last Jedi” to “27 Last Jedi moments that made no sense” to “237 reasons I hate The Last Jedi and You Should Too”.

There’s also a very natural social feedback loop that can work in tandem with this. I think for many people, it’s quite scary to make comments you think others will disagree with. If you found problems with something everyone loves, you’re less likely to shout about it; but if drama-optimising algorithms are showing more people that agree with you, that will embolden you to speak out more (see also: politicians making racist remarks emboldening racists).

My colleague Chris Hohbein saw this play out dramatically in the No Man’s Sky community. After that game’s launch, the community was incredibly toxic (mostly due to the game failing to meet their expectations); as updates to the game improved things, the hate diminished, and positive discussion flipped over to dominate the discourse instead.

Perhaps this doesn’t sound like that strong an effect. As a person who watches the first midnight showings of Star Wars films and feels moved to make comment on them in public right after, I can testify that the feeling of not knowing which way everyone else is going to go does make it feel a bit scary! That said, it’s Star Wars, I really should have figured out the pattern by now…

What I told you was true… from a certain point of view

Paradoxic Fandom certainly doesn’t apply to everything, and some of the above noted effects operate in reverse – for example, as in No Man’s Sky, confirmation bias can be positive; positive online conversation can beget more of the same.

But there are some particularly interesting counter-examples. For example, from that joke at the start, why is Star Trek different? And what about the ever-expanding Marvel Cinematic Universe?Are they doing things right in a way that others don’t?

In the case of Marvel, I’ve seen the argument that they play it “too safe”. In most Star Wars films, someone significant dies or loses a limb; Marvel films are frequently a battle to retain the status quo, and good guys and bad guys alike usually survive. So they entertain in the moment, but don’t do anything that might upset anyone. Over the last 10 years and 23 films, there have been a handful of notable exceptions from that, which seemed acceptable. Do they just have the right frequency of ‘not rocking the boat’**?

For Star Trek, each TV series will also tend to avoid disrupting its own status quo, but it’s unclear to me why subsequent series in different settings don’t seem to get as much hate as other franchise follow-ups*. This one is a mystery to me. Maybe I should become a Star Trek fan.

*Edit: I am reliably informed that I’m guilty of my own familiarity / contempt bias, and that actually Paradoxic Fandom is alive and well among Star Trek fandom. Prior to writing this, I had taken a brief look over various YouTube trailer comments, Reddits and forums to compare the Star Trek vs. Star Wars communities, and this seemed to confirm my hunch (or bias?), but this was hardly a rigorous study, and multiple people have now informed me of my error!

**Edit: This was written in July 2020. Since then the MCU launched Phase 4 which has been much less successful across various metrics, and is a whole other story. Still, it’s impressive they avoided negative feedback loops for so long and across so many films.

Conclusion: What do we do about it?

As a company / content producer

The biggest impacts on us as consumers are when things are better or worse than we expected. To the extent that you can, you want to exceed expectations. In practice this is tricky – if you hold your best bits or biggest surprises back from the marketing, perhaps fewer people will want the product. If you announce updates to an online game in advance and always under-play things, fans will spot the pattern and then be disappointed any time you fail to overdeliver. If you hold everything back, fans will worry nothing is happening at all.

To any extent possible, you can also be honest about things – educate consumers about the challenges you face. If you’re sure you’re right and they’re wrong, can you explain why clearly? Doing that – without making it an attack – can help both producer and consumer get closer to the more useful aspects of feedback.

More generally, I think it’s helpful to be aware of the above effects. Feedback from fans is extremely useful to help learn and improve; discounting it entirely is unwise. Knowing what drives it in different forms can help you unpick what’s most useful.

As a consumer / fan

I think a couple of Star Wars analogies help a lot here. As an engaged fan, do you choose the light side, or the dark side?

Luke: Is the dark side stronger?

Yoda: No. Quicker, easier, more seductive. […] A Jedi uses the Force for knowledge and defense. Never for attack.

You can use your deep knowledge of the material to engage in performative criticism (attack), or for knowledge and defence: what good-faith analysis can explain plot-holes? What practical aspects of production led to these compromises being made? What can we learn more generally about the craft from these decisions?

Luke: What’s in there?

Yoda: Only what you take with you

If you go in to a new experience ready to attack, you will find material to attack. Going in to anything new with an open mind, searching for elements to admire as well as those that justify criticism, is a more enlightening and fun way to go about things.

As an individual trying to find entertainment, I do think this is how you win – not by focussing on what you hate, but what you love. I distinctly recall spending the first 15 minutes watching The Force Awakens alternating between thinking “that’s not very Star Wars” and “that’s just a rip off of this earlier bit of Star Wars”, before realising no film could ever walk that line. With that in mind, I was able to enjoy the rest (of that film and the sequel trilogy as a whole) – while still finding a lot to criticise too! I find it highly rewarding to go in looking to enjoy everything I can, while also gaining enjoyment from engaging my more critical faculties later on.

There was just one more thing…

There’s a very important generalisation of Paradoxic Fandom. Consider these more generic forms of the regular mobile game complaints:

- Every change makes things worse

- This group/activity is failing and will die out

- Those making the changes are out of touch with participants

- Those making the changes don’t care about ordinary people

Does that sound familiar?

This is almost a textbook description of Populism in politics! The incumbent government is portrayed as out of touch with the people, that the country is failing, the government only care about themselves/the elite/the rich.

The country you live in has that same crucial quality we saw from “Exit, Voice and Loyalty”: it’s something you can’t easily change, and all the above listed effects can apply to politics just as they can to a game or multimedia franchise.

This means something! I just need a few more years to think about that.

Tim Mannveille tweets as @metatim, and sometimes writes about Star Wars on NothingAboutPotatoes

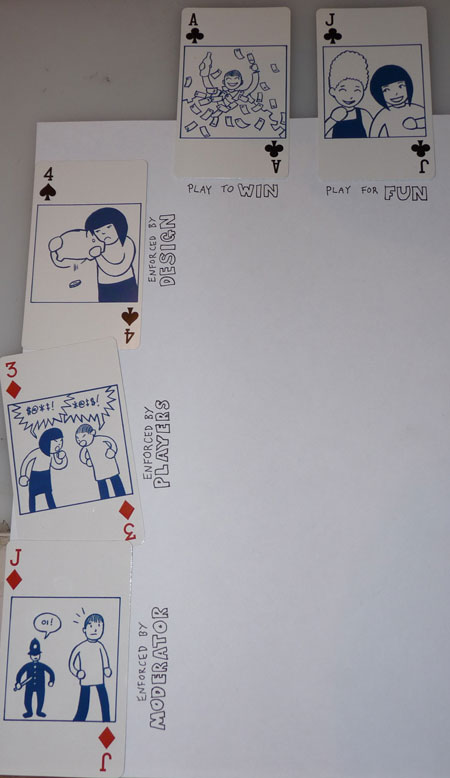

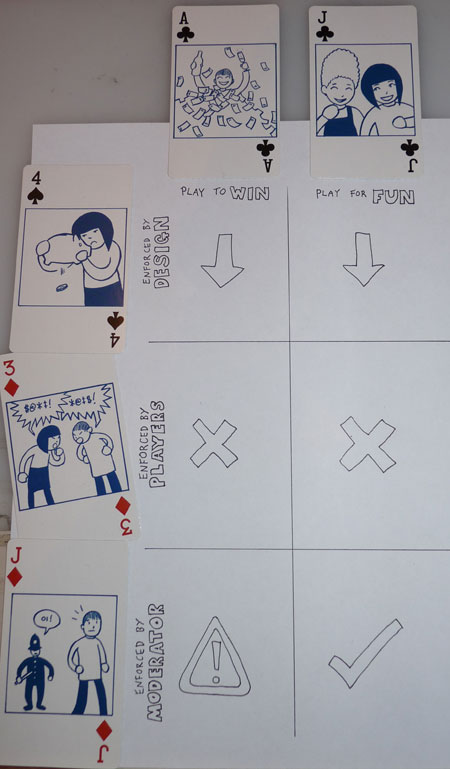

Let’s take a look at how cheating works across the 6 kinds of game this framework implies, and in particular whether choosing to bend or break rules is an interesting* choice for the players to make.

Let’s take a look at how cheating works across the 6 kinds of game this framework implies, and in particular whether choosing to bend or break rules is an interesting* choice for the players to make.