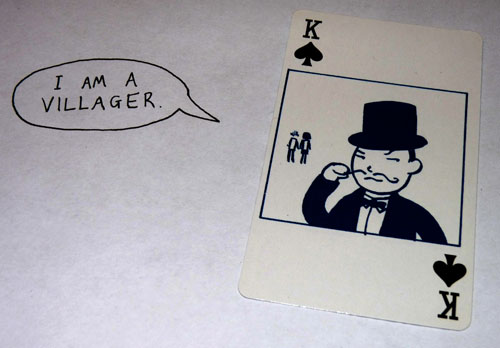

For no particular reason, these posts are illustrated using the Hand of Fate: Comic Strip Playing Cards by Karen Rubins.

At the recent Sandpit event at the National Maritime Museum, I played a game called Schooner or Later by The Haberdashery. A good game begets stories. This one begat many. In my case, it led me to an act of betrayal I didn’t even realise I was capable of. But to understand that, you need some back story.

As a child growing up in the late 80’s / early 90’s, TV shows like ‘Allo ‘Allo, Dad’s Army, and Frasier taught me that you should never lie, because if you do, you will be forced to lie about the lie in ever larger ways, people start opening doors at unexpected times and asking you ever more difficult questions, and, inevitably, hilarity ensues at your own expense, and then you have to admit that you forgot their birthday / ruined the dinner / taught the parrot to swear.

In some part due to these chilling fables, I grew up determined to always tell the truth and to be totally trustworthy. But that turns out to be impossible. So this is the story of how games taught me to get comfortable with that.

Cheat

In the card game Cheat, players take it in turns to lay groups of cards from their hand face down while declaring what those cards are. The following player can instead choose to call ‘cheat’ on the previous player, in which case the cards are checked, and the loser picks up the cards played so far. There is a restriction: you can only lay down cards (or claim to do so) that are adjacent to the most recent set played, so 2’s or 4’s can be played on 3’s, and so on.

While I understood what the game was about, I literally could not bring myself to ‘cheat’, even though it was part of the rules. If I ever found myself in a situation in which I had no valid cards to play, I would always choose to call ‘cheat’ on the most recent player rather than bluff myself. After all, if I started lying, people might start bursting out of doors and asking how the dinner was going, or something. Needless to say, I didn’t tend to do very well. But I felt as if I was playing honourably, and hilarity would certainly never ensue at my expense.

Extreme Cheat

On a sixth form school trip, we played a variant: instead of being restricted to cards adjacent to those most recently played, players could only ever play (or claim to play) 2’s. We played with two decks, and jokers were wild, so there were twelve 2’s in play, but nonetheless it was abundantly clear that players would have to cheat most of the time just to get anywhere. My never-cheat strategy was clearly going to backfire very badly here.

But something very interesting happened. One player, let’s call him Zippy, put down eight cards and said “Four 2’s”. The next player, who I’ll call George, called ‘cheat’, and turned over the top four cards, which turned out to be 2’s. George accepted his fate and picked up the whole pile.

I looked around at the other players – about eight of us. Almost everyone else seemed to know what Zippy had got away with, and nobody said anything about it. The game was called ‘Cheat’, after all, and apparently that meant that actual cheating was fine. With the bar raised in this way, I no longer had a problem claiming to play 2’s every time – but I never “really” cheated like Zippy did (or like others did later, by hiding some of their cards when no one was looking). Still, I had crossed an important threshold.

Poker (Texas Hold ‘em)

On that same sixth-form trip I played my first game of Texas Hold ‘Em, betting with monopoly money. I had a good feel for the probabilities, and with a little luck actually made it all the way to the showdown – me and one other guy, a guy who knew how to play poker properly. Whenever I had good cards he somehow knew it and folded. Whenever we were both in the pot he would win. I rapidly lost my remaining stake. I was playing half the game he was.

A few years passed and I next played Texas Hold ‘em at university for £1 stakes. The lesson had sunk in. I understood that everyone else playing understood that what you bid was only partially related to what you had; it also related to the impression you wanted to create about your hand, and even yourself as a player – perhaps you were trying to build a reputation as a certain kind of player that would influence your success much later in the game, or even a later game with the same players.

But here was the crucial part – you can always fold. I could ‘play’ with bluffing as much as I liked, but if it ever looked like I was going to be found out I could fold and no one would know I had ‘lied’ about my hand. Again, I didn’t do that well, but I got comfortable with the idea of bluffing – especially on those rare occasions when everyone folded and I took the pot with a losing hand, and somehow people failed to start appearing out of doors asking those difficult questions. It turns out that real life is not a sitcom.

The Turn

Around this time, I had an epiphany. I wanted to be 100% honest and 100% trustworthy. Then I realised that this was impossible. To be trustworthy, you have to be able to lie. If one person trusts you to keep something secret (“Don’t tell him we were talking about his surprise party”), and another person asks direct questions about it (“What were you guys talking about?”), at some point you will have to either lie or betray that trust.

Really, my sitcom training should have taught me this. ‘Allo ‘Allo has just about the most obvious example you could think of where lying is justified: resisting Nazi occupation! And if it’s legitimate there, then maybe it could also be the right thing to do in less extreme situations.

After some consideration I decided to go with being trustworthy, which meant I had better learn to get comfortable with lying.

Werewolf

In Werewolf (and its variants), players are secretly either villagers or werewolves. In the night phase werewolves secretly choose a villager to “kill” – to take out of the game. In the day phase, everyone argues about who they think is a werewolf, and they choose someone to lynch (take out of the game) on that basis. The phases and player killings continue until only villagers or werewolves remain.

Arguably even more so than Cheat, this is a game which depends on lying. The werewolves must claim to be villagers during the day phase to avoid being lynched, otherwise the game falls apart. It’s also a step up from poker when it comes to being perceived as a liar: instead of hiding behind folded cards, at the end of the game all will be revealed. Hilarity may well ensue.

In this context, with my training in Cheat and Poker, and thanks to my earlier epiphany, I finally realised I was willing and able to lie when necessary, and even got moderately capable at it.

I learned I needed to lie, and games gave me the opportunity to learn how.

But by a similar token, I could understand that sometimes in life you might have to break “the rules”. Clearly games can be designed around the idea of lying. What kind of game can actually teach you to cheat, or at least encourage you to bend the rules?

That’s what I’ll take a look at in the next post.

Tim Mannveille tweets as @metatim, and has previously written about Sandpit game experiences and a game based on cheese sandwiches.

4 replies on “Learning to Cheat Without Breaking the Rules, Part 1: Games about Lying”

[…] of. That got me thinking about the ethics of lying, what games taught me about that, and exactly how rules-based games can enable people to learn about breaking rules. The post is illustrated with playing cards, since that seemed […]

Hey! I stumbled across this by accident. Great to see my cards getting an outing. ^_^ Love the blog and the way you cover some very important (yet oddly trivial) topics like chocolate distribution!

Also, in your quest for lying games, I wonder if you’ve heard of Liar’s Dice. Quite similar to Cheat, but … with dice!

Hi there – thanks for the feedback, I was glad to put your cards to use! I was just thinking of illustrating the post with a regular pack of cards, it was only when I went through my drawers that I rediscovered the deck (which I think I purchased from you at the Web and Mini Comix Thing some time ago). I realised it was really quite the perfect set of illustrations for the job!

Funnily enough, at the Sandpit event that kicked this whole line of reasoning off I did actually play a variant of Liar’s Dice – I’ll touch on that in part 3 of this series.

Thanks for stopping by!

[…] Tower of the Octopus Over-analysis of Trivial Matters Skip to content HomeAbout ← Learning to Cheat Without Breaking the Rules, Part 1: Games about Lying […]