[This post was originally published in March 2013 on the blog of Stubble & Glasses, which sadly no longer exists.]

“Average [English] man has 9 sexual partners in lifetime, women have 4”

The Telegraph, 15th December 2011

I see a headline like the above every so often, and when confronted with such a significant finding (or any finding, or really just any number) the first thing I do is apply a sense-check. In this case, the result clearly makes no sense.

It takes two to tango

Imagine all men are on one team, all women on another, and the two teams are playing a very long, inadvisable, and poorly-thought-through game to see who can get the highest average number of sexual partners from the other team. The big problem is this: any time one team ‘scores a point’, shall we say, the other team necessarily gets a point too.

Since we also know there are roughly the same number of women as men, the game is always going to result in a tie: with each team fielding the same number of players and each team getting the same number of points, the average score has to come out the same. Cracked helpfully have some diagrams demonstrating this just in case you’re not sure.

So, the sense-check failed. Let’s understand this discrepancy, while keeping things completely Safe For Work.

Fix 1: Confirm figures at source

The Telegraph provided a citation. There, we find that the methodology is fairly standard, and that more specifically the figures are actually Men 9.3, Women 4.7. This means the male team is claiming a 98% higher score than the female (rather than the more dramatic original figure of 9 to 4, or a 125% more), but this is still a long way beyond the expected 0% difference.

Fix 2: Check assumptions

There’s one major assumption in the sense-check which you probably noticed already: that the figures quoted are for heterosexual pairings only. Fortunately (for the purposes of this analysis) according to the original study, they are.

Fix 3: Estimate loopholes

There’s a major loophole with the argument that the game should result in a tie: this is technically only true if we’re considering the entire viable population of the world. This particular survey only applies to England, so we should consider what we might call ‘away games’.

In the absence of data, let’s just make a rough guess and see where it gets us. What if 1 in 10 of the men’s scores came from away games, and only 1 in 20 for the women? (Of course, this is going to bias the figures the other way for the rest of the world, and the real figure might even be reversed – we’re just trying to get a feel for how much of the discrepancy this might explain).

Well, applying those adjustments would leave the men with an 87% higher score, at 8.4 to 4.5.

Fix 4: Allow for subjectivity

There is no referee in this game, which means there’s a certain amount of… interpretation as to what really counts. This could prove a highly diverting side-track if you were discussing this in the pub, but for now let’s just imagine men might overstate the case 5% of the time, and women might understate 5% of the time. This takes the score to 8.0 : 4.7, with the men down to a 70% claimed lead.

Fix 5: Misreporting due to societal pressure

Having corrected for any major discrepancies arising from the methodology, we’re left with one major problem:people lie. So, perhaps men are tempted to exaggerate and women to down-play their actual scores when it comes to number of sexual partners.

They say you should divide a man’s claim in this area by three, and multiply a woman’s by two – this overcorrects for the data we’re considering, but perhaps that’s because people are slightly more honest in a survey than in the casual conversation this rule of thumb is probably meant to apply to.

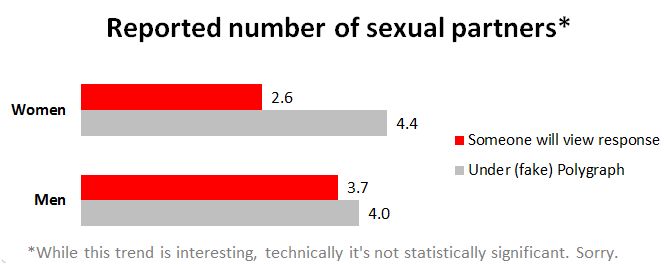

Fortunately, a widely reported study was carried out on exactly this effect. Men and women were asked this same question, but in different settings. Some were told a researcher may look at their answers, raising fear of social judgement. Others were hooked up to a (fake) polygraph machine, creating pressure to be more honest. (If you’re interested, check out the original paper here).

Women reported 2.6 partners when worried someone would look at the answer, but 4.4 under a fake polygraph. Men reported 3.7, but this went up to 4.0 under the fake polygraph. Ah-ha!

This is interesting because it suggests both men and women down-play their actual figure, but most of the discrepancy is coming from the women. If we apply these corrections to our estimated figures so far, we have men at 8.4, women at 8.0 – much closer.

Unfortunately the study was small (with just 200 participants answering this question), so while these particular results are suggestive, the researchers concede that they are not statistically significant. (As with any emotionally charged research subject, this didn’t stop the media reporting on the result as an established fact).

If you want to get technical about it

As well as being small, that study was only conducted on college students aged 18-25 in the US, who one would frankly hope behave somewhat differently to the general population of England.

Even in the original more robust English data set, there are some fascinatingly subtle problems. Sexual behaviour will change over decades (some of which is covered in the study), and the extent to which people lie about it will also presumably vary significantly by age. In combination with the fact that men and women have different life expectancies, and that cohorts by age group are not actually equal, this introduces some additional distortions to our assumption that we should see a tie – although a few quick calculations suggest these effects are likely to be smaller in magnitude than those we estimated above.

Okay but what’s the actual answer

This excellent paper goes beyond aggregated data to study the distribution of responses, and convincingly finds an explanation. It turns out that the discrepancy is driven primarily by those claiming over 20 sexual partners, because these rare-but-average-biasing individuals evidently round their score (which they may have difficulty remembering accurately) in the direction they deem to be more in keeping with society’s expectations – so men round up and women round down.

In Conclusion

If you skipped straight here, you should know that you missed some fun stuff where we talked about some subtle issues with the parity assumption, and you probably didn’t notice that that compelling-looking chart was actually not statistically significant. But if you just want the two-line answer, it’s this:

The overall average number of heterosexual partners has to be almost identical for men and women. The discrepancy found in studies like this arises primarily due to people with >20 partners rounding the figure they report, which they probably can’t remember exactly, up (for men) or down (for women), in response to perceived societal pressure.

More practically, always sense-check your data, especially if it’s self-reported and on a sensitive subject. And if you can’t make sense of the data, ask an analyst.