[After a 2 year gap, this finally concludes the story begun in part 1 and part 2 …]

When I was a kid, I couldn’t lie, I was terrified of breaking rules, and I was determined to be perfectly honest and perfectly trustworthy, not realising the two are incompatible. Years passed, and then in October 2011 I played Schooner or Later, and I flagrantly cheated and betrayed a complete stranger, much to my own surprise. Perhaps even more surprising, I found that I was actually okay with this.

Right after that I started a series of posts on the subject of lying and cheating, how both are important and justified in some situations, and how games helped me learn to do those things when necessary. But I stalled on the final post, which was intended to examine the specifics of my betrayal in Schooner or Later. This is hardly satisfactory, especially considering I actually interviewed one of the main creators of the game, Josh Hadley, for the purposes of that write-up.

So, it’s time to face up to my past: this is the final part in the series, describing what happened that night, alongside commentary from Josh, which I think endorses my actions.

Of course, I may be wrong about that.

So, long ago, on the 13th October 2011, there was a Sandpit event at the National Maritime Museum, with a bunch of maritime-related games.

One of these was a variant of Perudo (called Filthy Lying Liar’s Dice, by Gareth Briggs), in which everyone rolls their dice (which in this case corresponded to parts of a pirate ship), and then plays a kind of cumulative variant of Cheat. Losing a round means you lose a die, reducing your ability to understand the state of the game. Thanks to my training in lying-related games (as detailed in part 1), I did pretty well, making it to the final showdown, albeit with a single die.

Playing the game with strangers, I noticed something I hadn’t seen before when playing similar things with friends: despite everyone bluffing / lying and generally trying to harm everyone else’s chances of winning, a sort of camaraderie developed, and by the end we felt somehow unified. If you administered some sort of trust test, I imagine we would all trust one another much more than we had at the start, despite playing a game that hinged on misleading one another. Perhaps this is related to the fact that you can only trust someone with a secret if you know they can lie if asked about it.

Anyway, at the end of the evening, most of the players (about 35 of us) were funnelled into the final game: Schooner or Later (SoL) by The Haberdashery, in particular by Josh Hadley and Casey Middaugh. In part 2 of this series, I argued that moderated games played for fun were the best type to let players explore cheating. Various aspects of the game design and the running of SoL meant an entire spectrum of cheating was available, and even implicitly encouraged. By my count, we saw 7 levels of cheating that night, each more flagrant than the last – and when I asked him about it later, Josh said he was happy with all of these bar one.

Schooner or Later – the basics

At a base level, SoL is a trading game. Players travel between three ports – England, India, China – buying and selling commodities and trying to turn the greatest profit within the set time limit. But that’s just the framework: the actual execution of the game encouraged cheating of every type.

Josh on cheating

When I asked Josh his thoughts on cheating, he answered immediately: “I try to make games where cheating is an interesting and viable approach – it’s something I consciously try to involve in every game that I game.”

He dates this back to when his family used to play Monopoly (which he characterised as “the worst game ever inflicted on humanity”), in which the only way they could make it tolerable was by introducing a house rule: “anything is permitted so long as you don’t get caught out” – just like “Extreme Cheat” that I mentioned in part I.

(Incidentally, the history of Monopoly’s development is quite illuminating).

Even against this backdrop, Josh thought SoL was special: “This game encouraged cheating, almost as a design principle.”

He also thought the theme was appropriate, and was what encouraged him to add in ‘cheating’ elements: as part of the East India Trading Company, “everyone was a gigantic bastard”.

I think that’s very interesting. How do you make a game in which everyone is supposed to be some kind of oversized bastard, given that it will be played by players who may not personally be any kind of bastard at all? Here’s how.

SoL Cheating, Level 1: Opium smuggling

The primary twist on basic trading in SoL is a mechanic that feels illicit, but you are expected to do it (like lying in werewolf). Players can choose to ‘smuggle’ opium, manifested in-game as balloons, from India to China. Two moderators took the role of coast guards trying to prevent the opium trade by popping the balloons of players they could catch.

The layout was excellent for this: there were three smuggling routes to choose from, and two coast guards, so you could usually find a way.

Because of the sneaking necessary, and the compelling stand-in for real violence of balloon popping, choosing to smuggle had the feel of being illicit – but the rewards for success were so substantial that it was hard to resist. Besides, when playing for fun, you want to try everything out. Perhaps at the start of my personal journey – before I had played Extreme Cheat – I might have tried to go ‘legit’ and trade only the regular goods. But as a result I wouldn’t have stood a chance of winning, and I certainly wouldn’t have had as much fun.

Josh noted that there is supposed to be a tension between the opium and standard economic game, with an emergent strategy on when to switch – but he was also curious: as a player, do you think about what you’re doing, in an ethical sense?

With opium trading explicitly written into the rules and briefed, I’m not sure many players spent that much time worrying about this. However, that ambiguity is certainly present in the many further layers of cheating that the game’s design encouraged. For example…

SoL Cheating, Level 2: Cotton dumping

The second twist was somewhat surreal. England wanted to trade cotton (represented by cotton wool balls), and any time you made a trade of goods there, they would insist that you take a handful of cotton wool and try to sell it to India or China. Furthermore, any cotton you were left with at the end of the game would count against your score.

But India and China didn’t want the cotton – they certainly wouldn’t give you money for it, at best they might grudgingly accept it. The cotton wool balls also take up room in your hands, making it harder to get on with the real business of trading tea and pepper, or smuggling Opium.

This means you’re incentivised to “lose” your cotton en route – but the rules don’t say anything about that. Can you just drop it? Do you have to hide it? Give it away to non-players? Having a quirk like this built into the rules is an effective way of making the players aware that they should be creative.

Josh confessed that this broke the rules for a Sandpit game, in that the game design encouraged littering (“I’m fairly sure there’s still wads of cotton wool bunched up behind exhibits in the National Maritime Museum”), and while they paid lip service towards telling people not to do it, they knew it was inevitable.

As well as meeting his goal of encouraging ‘cheating’, Josh also noted that this is actually a historic truth – the majority of the captains did pitch their cotton overboard because they had the same incentives as us! (I’ve not found a good citation for this, sadly).

SoL Cheating, Level 3: Haggling

Haggling was not mentioned in the verbal briefing, but explicitly encouraged in the instructions. Any player not noticing this would quickly cotton on (ho ho) once they heard the haggles going on at the various ports.

What are the rules of haggling? Only what you can propose, and what the other will agree to. There seemed to be a little flexibility in the price, but it seemed you would do a lot better with a more creative approach – for example, pointing out that making it a round 100 would mean they could hand over a single 100-worth token instead of counting out the 90 in the asking price. In this way, the moderators (as the operators of the ports) were actively giving the players cues on how to play, and proving that the game was flexible.

SoL Cheating, Level 4: Co-operation

The fourth twist (in my somewhat arbitrary ordering) was co-operation. The results of haggling suggested that greater quantities of a good yielded bigger discounts. This created an incentive for players to work together, pooling their resources to get a bigger pay-off. Of course, where co-operation is possible, so too is defection.

Why I’m a big cheater, and that’s okay

Having enjoyed the “cheating” of dumping cotton wool (I bestowed it upon a friend who wasn’t playing), smuggling opium (surprisingly frightening but very rewarding), and haggling, I was getting the feeling that the boundaries of the game were open to question.

When I realized both I and another player at port in China had 47 gold and we would each be offered 6 tea in exchange, I proposed we pool our resources to better haggle for more. With this plan agreed spontaneously in front of the port moderator, we were offered 13 tea rather than 12. We pointed out that 14 would be much fairer as then we could divide it by two.

“Not my problem,” came the reply. “You’ll have to work it out between you.” We looked doubtful, not sure how to resolve this fairly.

“Put your hands out, ” said the moderator, and I did. He put the 13 tea bags in my hands.

Then he looked me in the eye and said: “Run!”

This was the magic moment for me. When you’re playing for fun, and taking your cue from the moderators as to what’s allowed, how do you react to a direct prompt like that? How would I?

I said “I wouldn’t do that, I’m an honourable trader,” and turned to my compatriot: “Here’s 3 tea for you. Bye!” and to my own surprise, I made off with the other 10. “That’s not honourable!” my former compatriot replied, “Come back here!”

We both made port at England, at which point my former compatriot attempted to seek restitution from the authority there. Upon understanding the situation, England’s port moderator simply said “I’m sorry, this is clearly an internal matter. I can’t help. I’ll give you 95 for your 10 tea.” Another endorsement – I felt like I’d been bad (which I had), but somehow within the spirit of the game, if not within the letter of the rules.

As I wrote in part 1, I started out in life so determined to be a ‘good’ person, I wouldn’t cheat even in games where cheating was the point (like “Cheat”). The fact that I cheated another player so brazenly here really shocked me, and that’s why I started writing this series of posts: to understand what sequence of events – actually, games – brought me to this place.

But given that I also interviewed one of the key designers of the game, and that I put off writing this particular moment up for 2 years, I’m suspicious of my own motives. These posts could all be read as one big attempt to excuse my decision that day, and talking to Josh may just have been a subconscious attempt to have my actions endorsed.

Fortunately for me, that is exactly what happened.

Josh’s comment was “That’s a great story – I’m really pleased by that!” – and he reaffirmed that he had hoped players would think about the ethics of what they were doing, and question their decisions in just this sort of way.

He also particularly praised the Haberdashery crew for creating the environment that made this work: “We could only give the players freedom if we also gave the crew freedom. So long as you have a good crew – and we had an amazing crew – you have a huge amount of leniency to encourage and permit that kind of behaviour.” Crucially, he pointed out, the Haberdashery crew know how to “manipulate rules without necessarily breaking the game.”

But cheating in SoL didn’t stop there.

SoL Cheating, Level 5: Syndicates

Other players went much further. Beyond short-term co-operation, a few players actually formed syndicates: they pooled their resources, ran interference to facilitate smuggling, and declared a collective score at the end rather than an individual one.

I had the impression that the players that did this already knew (and trusted) one another outside of the game, but I didn’t feel hard done by: it felt like a logical extension to the game. Josh in particular was really pleased by this development – it’s something he had hoped would emerge, and this was the first run of the game where it actually happened (perhaps because the scale was so large, with 35 players).

SoL Cheating, Level 6: Role-play

As another clue that this was no ordinary trading game, one of the moderators running trade at China began to act as if she was succumbing to an opium addiction. I heard from Josh that a player took advantage of this by withholding opium in order to secure a ridiculous bulk discount on tea, allowing them to actually buy All the Tea in China. When the player presented this haul to England, they received what Josh described as a “frankly insulting amount of money”, but nonetheless profited from their wilyness.

Josh considered this another example of the Haberdashery moderators knowing just how much they could bend the rules: they had been specifically briefed that they were empowered to deliver whatever they thought was a good experience, so long as it didn’t break the game. In particular, he admired the way the moderator at India (Ruth) could appear out of control while actually being fully in control, and the moderator at England (Nick) could give the appearance of being inflexible while actually bending the rules as much as anyone. This extreme event briefly impeded normal trading of tea, but this was swiftly fixed.

SoL Cheating, Level 7: Stealing!

The final level of cheating was achieved by a player who flat-out stole some pepper from India when the moderators were distracted. I’m not sure Sandpit players would usually stoop to that sort of behaviour, but in the context of everything else that was going on it must have seemed reasonable.

But this was where Josh drew the line – crucially, with this type of cheating, the moderators were no longer in control of the game. When this happens, “it stops being a game, and becomes a free-for-all”. Fortunately, this didn’t generate a substantial advantage, unlike the syndicate of three players running their Opium smuggling ring who ultimately “won” the game.

Epilogue(s)

One player decided to “corner the market” in cotton wool, and had been collecting it at every available opportunity, storing it in his hat:

He was duly congratulated as the “true winner” and received a round of applause. After all, he had played for fun, and he had certainly succeeded at that.

While the scores were being collected, I overheard one player lamenting how it could be a perfectly reasonable game if it weren’t for all this “cheating”, and that people should just trade according to the rules. Most unfortunately, this turned out to be the very player I had betrayed earlier. I introduced myself, and apologised, but tried to defend myself by saying “Of course, once you saw how the game could be played, I’m sure you went ahead and did similar things yourself,” to which he replied “No, I traded entirely by the rules.”

This was difficult. I felt as if I had to justify my decision somehow, but rather than try to explain the entire argument put forth in this series of posts (which I was only vaguely perceiving), I simply passed the buck: “Well, you saw what happened – I was encouraged to do it. He just shoved the tea in my hand and told me to run. At least I gave you some.” At this he grudgingly admitted that that was true. Only at this point does the role of the moderator end: when their judgements are used by players to justify their decisions.

Finally, one pair of players had to leave before the final scores were counted up – and they happened to have been playing the Liar’s Dice variant with me earlier that evening. For whatever reason, they chose to bequeath their accumulated in-game wealth to me.

I like to think that they felt they could trust me, even though I’d been proved a liar.

Of course, I may be wrong about that.

[Update below added 8th May 2022 – T.M.]

Postscript, 9 years later

The definitive conclusion of this journey came in 2022. As part of the panel in a work recreation of ‘Would I Lie To You’, I was required read out loud a card with part of a story or anecdote, not knowing in advance what it would say, and then justify to the opposing panel and audience that this was a true story from my life.

More specifically, if it was a lie I had to make it seem truthful, and if it was true I had to make it sound like a lie.

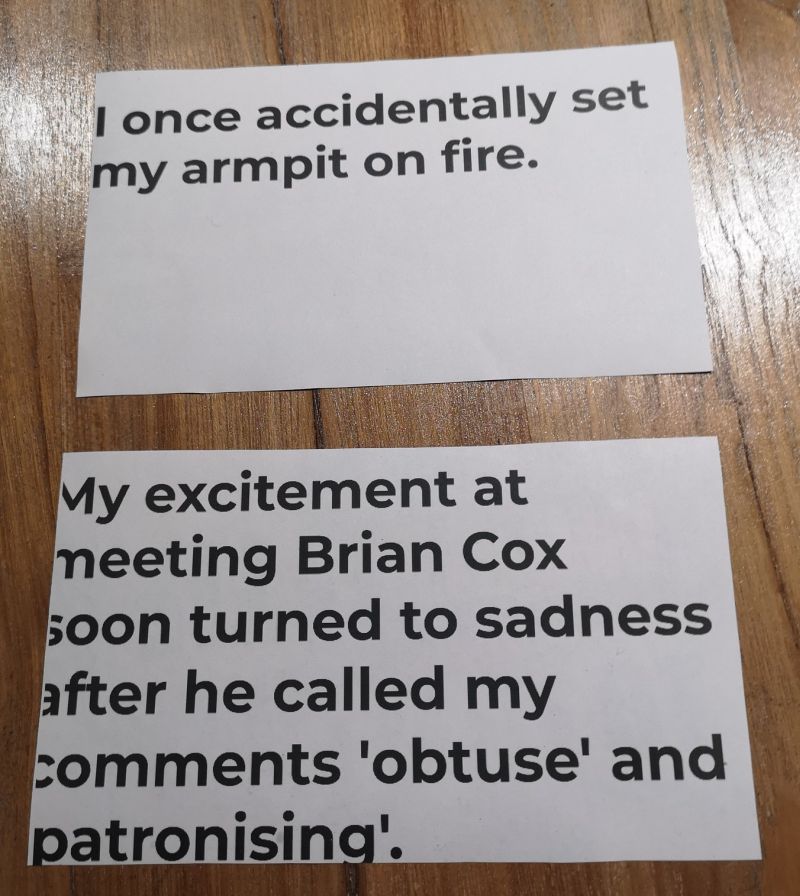

Each participant had two cards, and these were mine:

Either or both could have been true or false; as it happens I got one of each. Most amazingly, and with only a little luck, I convinced the opposing panel that the lie was true and the truth was a lie.

My journey to become a person who you can trust to lie if necessary is now complete!

Tim Mannveille tweets as @metatim, and has previously managed to blog about a sandpit event much more quickly than this.