The Message

On Wednesday, nobody died. It took a while for people to figure this out.

On Thursday, the moon disappeared. As far as scientists could determine, in its place was a very small object of equivalent mass. This caused quite an uproar, so when the news about nobody dying came out it didn’t get much attention.

On Friday the moon reappeared/re-grew, and by this point some countries had figured out that the period when nobody died on Wednesday was exactly 00:00-23:59 UTC, which seemed pretty weird.

Then the message came.

All humans over the age of 23 years, 11 months and 6 days received it simultaneously, even if they were asleep. None could recall if they heard it as words, saw it as images, or experienced it some other way – but everyone agreed on the content. After claiming credit for the miracles just witnessed, the message set out the following ultimatum:

- In 64 days, everyone who receives this message will vote

- The choice is between red and blue

- There is no inherent meaning in the choice

- If more than 62% of voters make the same choice, regardless of whether it is red or blue, humanity will be welcomed into the galactic community of sentient beings and, gradually, be allowed to share in highly advanced scientific knowledge

- If fewer than 62% of voters make the same choice, humanity will be instantly eliminated. The rest of life on earth will carry on.

The message was understood clearly by all, including speakers of languages lacking a word for ‘blue’, the blind, and the cognitively impaired. In news reports the message quickly came to be called the Consensus Ultimatum.

Some individuals – mostly scientists – received a bespoke version of the message, further explaining that in the period leading up to the vote Earth would be protected from certain specific threats; threats that these individuals were best qualified to comprehend. Pooling this knowledge yielded some well-known threats (solar flares, errant asteroids, novel contagious diseases, miscellaneous climate disasters), as well as other threats not yet well understood (most notably: water decay, localised vacuum collapse, catastrophic crust failure, and all categories of crab singularity). Should humanity pass the test, these protections would continue.

Initial Responses

A lot of people thought this would be easy, on the basis that a consensus should quickly become clear, and this would create a feedback loop ultimately driving well over 62% of people to vote for it. Some of the more cynical thought this level of consensus may be hard to achieve; a few judged it impossible. But it was almost universally agreed that an active effort should be made to try to reach consensus.

A very small minority preferred that humanity fail the test and be eliminated.

First Steps

A commitment to vote a particular colour quickly began to trend on social media. Within different language and cultural bubbles, different colours tended to win. Once a winner became clear, a strong social-proof effect meant that a bubble would quickly favour one colour with a consensus of ~80%-90%.

In the US, the social media trends generally aligned with political leaning: left-leaning voters sided blue, right-leaning red. In the UK, these were reversed in accord with their local colour associations. Many other countries followed this pattern.

Within a couple of days, government recommendations – or in some cases mandates – began to come out. After some deliberation, the US democratic president announced that American citizens should choose red. They expected fellow democrats to take this lead regardless of the political undertones, and assumed republicans would be happy to go with the colour their bubble had already selected. They also anticipated that China would favour red.

Indeed, one day later the Chinese government announced that their citizens would vote Red. The cultural associations made it a clear favourite. Other nations made similar announcements, most – but not all – favouring red.

Many nations began to roll out surveys to establish current voting inclinations. Seven days after the message was received, humanity’s collective best guess was that about 65% would vote red, 12% would vote blue, and 23% had not yet heard any guidance. Early modelling suggested the unknown portion would fall out roughly 2/3 for red; this gave a first estimate of an 80% consensus for red.

Collectively there was a feeling of cautious optimism. Some countries began outreach programs to spread voting guidance to isolated populations, and there were several international surveying efforts on top of the quickly established national programs.

Non-Governmental Movements

Various crowdsourced efforts began to gain traction, most notably:

- Trends in modifying social media avatars to indicate intended vote

- Raising money to supply guidance to populations being overlooked by official routes

- Crowdfunding for ad campaigns to swing regions looking least likely to align with the consensus

Several competing DAOs formed with the goal of storing everyone’s publicly-declared vote on a blockchain. The immutability and public nature of the blockchain made this superficially appealing, but arguments about vote-changing rights and a failure to get close to the coverage and reliability of standard survey techniques prevented these solutions from reaching the mainstream.

Some billionaires took the ultimatum as their cue to save humanity. Bill Gates initiated production and distribution of extremely cheap solar/hand-cranked radios, so anyone out of reach from traditional media could be updated on the consensus as the deadline approached – but debates on the editorial control of the broadcast limited the effort to a subset of the target countries. Elon Musk announced a plan to put 8 billion LEDs on the Moon and give every human on earth a digital switch to set one of them to red or blue, so the consensus would be immediately apparent; people said it couldn’t be done, and they turned out to be correct.

Message Interpretations

It did not take long for people to question the true nature of the Consensus Ultimatum. A few theories began to gain traction.

The character test: the belief that the vote would not matter as much as humanity’s response to it. This might explain the rather long period of 64 days between the announcement and the vote. There was not much agreement on what behaviour was more likely to pass the ‘true’ test at this stage.

The prank: the message was just some kind of joke by a highly advanced being or civilisation. They may or may not follow through on the ultimatum; other beings/civilisations may find out about the prank and intercede.

The fix: this theory held that a galactic – or even wider – vote was due to be held, the consequences of which humanity had no conception. The Consensus Ultimatum was a form of lobbying by some part of the galactic community that had analysed humanity and concluded this would push the vote a certain way, without violating some rules of interference. The general conclusion was that this amounted to a variant of Pascal’s Wager, and humanity should take the ultimatum at face value anyway.

The denial: popular among those too young to receive the message (particularly those on TikTok), but also among some adults, this group held that it was all an elaborate hoax that had got out of hand, or perhaps a conspiracy by a shadowy but earth-bound elite to exert control via unclear means.

Anti-consensus: people who suspected that it was a trap, and the consequences might be reversed; that humanity would be eliminated if it reached too high a consensus. Perhaps the galactic community had bad experiences with populations that were too easily aligned to a single cause, and this test identified them for elimination before they caused trouble. Voting against the dominant consensus was the best way to survive.

Moderate consensus: these people held a similar belief, but thought there was likely an upper limit. A consensus above 62% was fine, but if it was too high – over 90% perhaps – this would be taken as a bad sign and humanity would also be eliminated.

Consensus begins to weaken

Just one week after the message, the idea of voting against the emerging consensus for red began to spread among certain groups. This included some believers in the anti-consensus or weak consensus ideas, but also those for whom the general appeal of rebellion was particularly strong. A natural inclination to distrust the government extended to distrusting this apparently higher, presumably alien authority.

A significant minority in the US in particular announced plans to go against consensus; when the ‘aliens’ came to eliminate humanity, they would be ready to defend themselves with their own arsenal. The idea that a culture capable of suspending death and shrinking the moon could be resisted with ballistic weapons did not seem plausible to anyone else. However, among those who favoured this line of thinking, conspiracy theories regarding those earlier ‘miracles’ began to gain traction; a friend of a friend knew someone who died on the supposedly deathless day; photos of the moon purportedly from the day of its disappearance were also widely shared. This group banded together under the banner ‘True Blue’, in defiance of the emerging consensus for red.

Various other conspiracy theories also began to take hold among this group. Core components of these theories generally took the following forms, without regard for self-consistency:

- Globally, blue is a more popular colour than red, so would win naturally despite any government messaging

- The push for red was designed to offset the natural inclination towards blue, pushing humanity towards non-consensus and elimination. The elite would escape by travelling to the moon / mars, and then return to inherit the earth.

- The elite had secret knowledge that the message was a lie, and that red voters would be eliminated while blue voters would survive. The push for red was a plot to thin the herd.

- Alternatively, the elite had secret knowledge that the message was more of a misdirection, and whoever voted for the minority colour would be eliminated. The push for a red majority was a gambit to eliminate the non-compliant blue-voting population. The best way to fight back was to ensure the majority was blue instead of red.

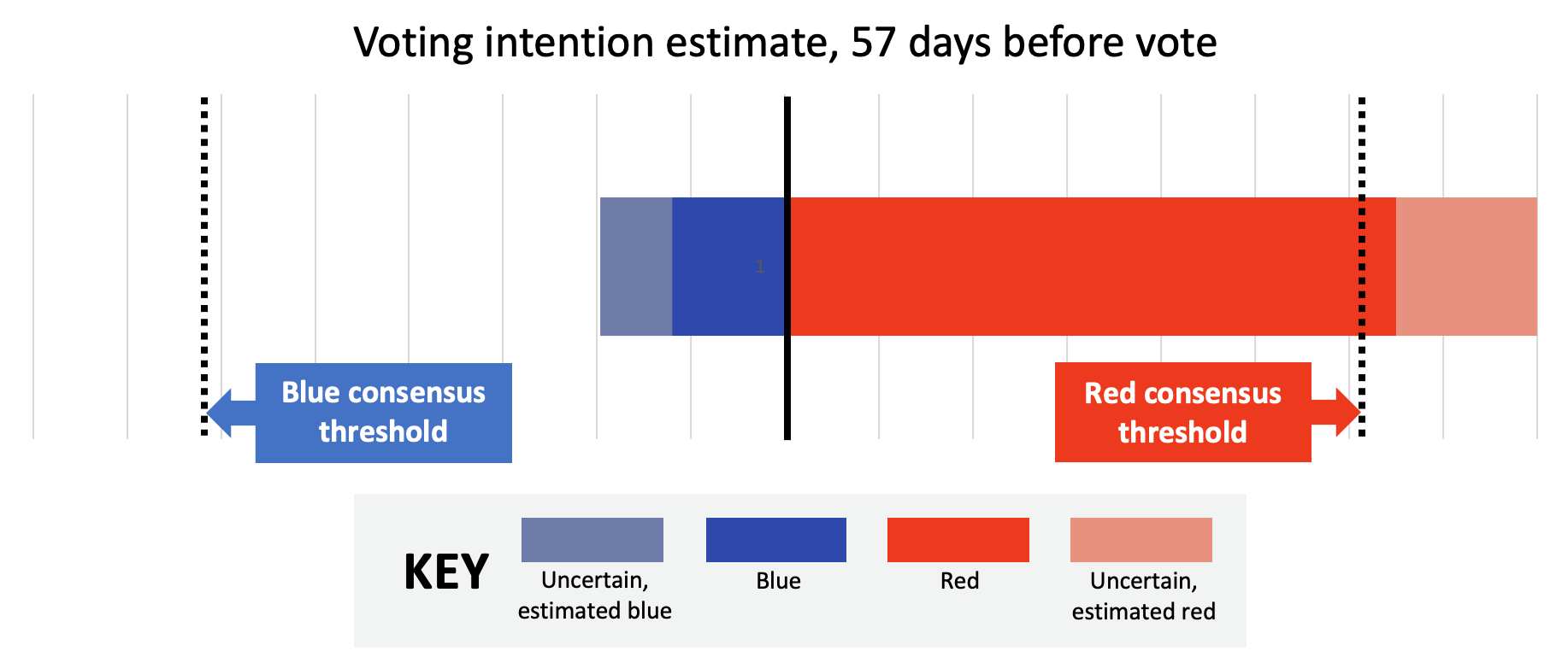

Three weeks after the message, the last major country finally made their decision: Russia came out in favour of blue, for unclear reasons. With a population under 2% of the global total, this was not perceived as too much of a threat to consensus. That said, consensus certainly had weakened; estimates suggested the results would be:

- 70% Red

- 22% Blue

- 8% Unknown, but perhaps 70% of these for Red

This gave an estimated consensus of ~75.6% for red.

At this point it is worth noting some other large-scale behaviours that deviate from the no-message paradigm, which we term ‘distractions’.

Distractions

Interest in space tourism picked up as some began to investigate the best method to get themselves and their loved ones off planet for the time of the vote, despite this not allowing them to escape their fate in any way. Interest in more traditional but equally ineffective bunkers also boomed.

Scams proliferated almost immediately, such as:

- Fake bunker investments

- Elimination insurance

- Spoof government vote-registration links for phishing purposes

- Incentive programs offering cash in return for a red vote (with an up-front fee)

- Gurus who claimed to be receiving follow-up messages and charged for their insights

Progress towards mitigating climate change stalled on multiple fronts as many people considered it moot; it would either be solved, or humanity would be eliminated.

Several new research fields were initiated to investigate the poorly understood threats some had learned of from the message. The obvious approach was to identify the areas of expertise shared by those informed of each threat, and then use that to infer the nature of the threat itself. This proved almost entirely fruitless; for example, those notified of the crab singularities consisted largely of marine biologists, computer scientists, and a professor of experimental literature. The one exception was water decay, which was then accidentally initiated in an experiment. The water sample and the apparatus used to create it disappeared; the experiment was indefinitely postponed.

The overall economic impact was chaotic. Work resignations rose as the vote drew nearer, and there was a marked increase in more expensive recreational pursuits; many expected that humanity would be eliminated when the time of the vote came (or would perhaps be ushered into some sort of golden age), so they might as well enjoy themselves. Consumer saving (especially pensions) began to fall off while house sales and borrowing accelerated. Stocks and other assets were sold off at an increased pace, leading to market crashes. Irrational panic buying affected various goods in different regions – often fuel, but in some cases ammunition, food, e-scooters, and contraception. Some governments accelerated borrowing, others lending, all depending on levels of optimism for consensus and different approaches to risk mitigation.

Many countries with weak consensus proposed emergency laws/elections, and in extreme cases were subject to coups – all with the stated aim of improving the consensus. These political upsets interacted with the unprecedented consumer behaviour to drive novel effects not previously known to human economists, such as predator-prey public/private feedback loops, organised crime microbooms, and, inevitably, non-transitive Gödellian asset violations.

The Turn

As the weeks rolled on, the idea that some nations might be able to profit from the vote began to gain traction.

Most benignly, there was a subtle dilemma regarding surveys. Some advantage could theoretically be gained by being less public about survey results: less clarity on voting intentions could spur other nations or organisation to make greater efforts to ensure consensus. For example, if global consensus was estimated at 75% ± 2%, little effort further effort might be made; if instead it was 75% ± 10%, the motivations would be stronger. Since the direction of consensus (red) was already obvious worldwide, a more exact measure of it might actually do more harm than good.

Less benignly, that reasoning could be extended further: actively underreporting intended votes for red, at least to a certain extent, could lead to better consensus efforts by others.

We refer to the nations with the strongest leverage in these regards as the Quiet.

At the same time, it became clear that any sufficiently large nation with strong control over its media could use this strategically: they could declare that they would only issue guidance for the current consensus if certain international agreements were changed. It was widely assumed that this was why, three weeks out from the deadline, China (representing 18% of humanity) announced it was suspending guidance and would advise citizens how to vote nearer the time. This move was swiftly mirrored by smaller nations with similarly strong media controls. No demands were made; the official reasoning was that they considered it prudent to decide their guidance when greater clarity on consensus emerged. We refer to this group of nations as the Undecided.

(Of note, while India similarly accounted for around 18% of the population, it was considered to lack the survey accuracy or media control to gain significant leverage as part of the Quiet or the Undecided).

The strategy of the Undecided incentivised the strategy of the Quiet and vice versa, resulting in a Nash equilibrium of global consensus uncertainty.

Final weeks

At an individual level, alignment with each colour calcified. Communities that had previously shown flexibility while a dominant colour was emerging now associated the colours with distinct tribal identities. Despite the emerging greater importance of switching to achieve consensus, to do so became a threat to group identity.

The economic effects began to accelerate. Both products and services widely saw a 15%-20% decline in the commencement of any projects due to start after the date of the vote. On top of this, voluntary unemployment was starting to climb above 10% in many nations, causing food/service shortages and significant supply-chain issues. Alongside the tension regarding tribal colour identities and the debates on the Quiet/Undecided strategies, some countries drew close to civil war, but in most cases avoided it.

Among the more powerful nations, serious consideration of more aggressive interventions began shortly after the emergence of the Quiet/Undecided dynamic. In the anticipated negotiations between data access from the Quiet and citizen voting mandates from the Undecided, a stick could be as good as a carrot. Notably, a very simple method could be used to tip the balance: the mass elimination of nations or peoples expected to vote against the desired consensus. With the fate of humanity on the line, some saw this as a moral imperative.

Three types of aggressive intervention were considered.

- Most obviously, proven technologies or processes, such as nuclear weapons and state blackmail.

- Speculative research programmes that could potentially make rapid progress with accelerated funding, such as weaponised drone swarms, large-scale sonic weapons, and targeted viruses. However, the timescale limited meaningful progress on these fronts. Attempts to weaponise water decay were naturally fruitless.

- We will cover the third intervention category in the next section.

Endgame

Two weeks before the day of the vote, the Undecided made their move as a collective: they would direct their citizens to vote red (so exceeding 62% consensus globally) on the condition that the Quiet first reveal their survey data, and – more significantly – that after the vote any newly revealed technologies should be preferentially shared with the Undecided. China’s unique position of an extremely large population and a tightly controlled media meant they could push for concessions most credibly.

There were two clear problems with such a request.

If there was a chance these demands could precipitate a consensus failure, all would be moot, as failing to reach the consensus would mean the elimination of all humans.

Secondly, there was no obvious way to enforce the sharing of new ideas. The widely anticipated method of knowledge dispersal would be a variant on the message: just as those with the knowledge to comprehend them were advised of specific threat protections, presumably those best able to understand the new knowledge would receive it in much the same way.

This drawback was anticipated by the Undecided.

There were layers of proposals to gather this information, ranging from the clearly unacceptable to the rather mild. For example, at the time of the message, many humans were undertaking various forms of brain activity monitoring, almost all of which subsequently showed distinct patterns as the message was being received. One proposal therefore required the continuous surveillance of brain activity of all scientists, followed by the prompt sharing of any information received. As a step down from this, all scientific journals could be required to run paper submissions through a panel composed of top scientists from the Undecided ahead of publication. At the mildest end of the spectrum there was a proposal for an annual, global conference for all new knowledge gained, to be held in Beijing.

The stakes of this negotiation were also lowered thanks to a graduated approach to messaging. The Undecided had earmarked each of their component nations (or individual regions in the case of China) for separate, timed broadcasts on vote guidance that could be issued one way or another, depending on the progress of negotiations. This could play out against similarly incremental concessions from the Quiet.

Negotiations began, with all aspects of the above on the table.

More traditional points of negotiation such as trade and energy agreements were less important, as their existing complexity could not be addressed under the tight deadline of the vote.

The threat of more drastic interventions formed a more subtle part of the negotiation process. The prospect of mass population elimination receded as the ‘character-test’ hypothesis gained general acceptance: it seemed likely that mass warfare would disqualify humanity from the test, regardless of the vote. However, a plausible threat of less deadly interventions could still drive an advantage at the negotiation table.

In the final days, various unusual hazards emerged in the most prominent negotiating countries, and it was widely assumed these could be read as threats; this is the third category of aggressive intervention. The most notable examples of this were as follows.

Disappearance in Australia

A prominent minister on the Australian National Security Committee disappeared overnight, along with their close family. More significantly, their digital presence was erased at the same time: Facebook accounts deleted, Wikipedia entries (and even their edit histories) removed, personal websites deregistered, records removed from Ancestry.com, and historic online articles from many large news sites disappeared. Less obviously, the minister’s pre-emptive obituaries held on standby by many national news organisations also vanished, and even their remarks in the Australian parliament’s Hansard unaccountably disappeared, leaving almost no digital trace they had ever existed.

Demolition in China

In China, the broadcasting system in two residential tower blocks in different cities unexpectedly issued an evacuation order; fifteen minutes after the evacuations, the buildings collapsed without apparent cause. This coincided precisely with the unexpected collapse of three large tower blocks in a ghost city, which had been scheduled for demolition in several months’ time – but before any explosives had been planted.

Isolation in the US

In the United States, a relatively small town (population 8,000) found itself cut off overnight in more ways than one. Seemingly natural incidents blocked all roads in and out (bridge collapse; fallen powerlines; localised flooding due to a burst water main). Telephone, electricity and internet access were also cut off. The mayor and deputy mayor both fell ill with flu-like symptoms, as did the chief of police and half a dozen other local leaders. It was only after contact was re-established 24 hours later that further, more troubling aspects emerged. An unusually large number of people who had planned to visit the city that day had changed their plans for a wide range of reasons, and most of those who stuck to their plans ended up turning back on encountering the obstacles. Many friends and relatives of the town’s population received normal-seeming text messages or saw plausible social media posts from them that they had never actually sent – and often these spoof messages served to dissuade or delay planned visits to the town.

While nobody claimed responsibility for these incidents publicly, subsequent analysis of the ongoing negotiations between the Quiet and the Undecided suggests that these were indeed instigated deliberately and were meant to demonstrate capabilities which could be unleashed at a wider scale; as such they served to boost their respective nations’ negotiation position.

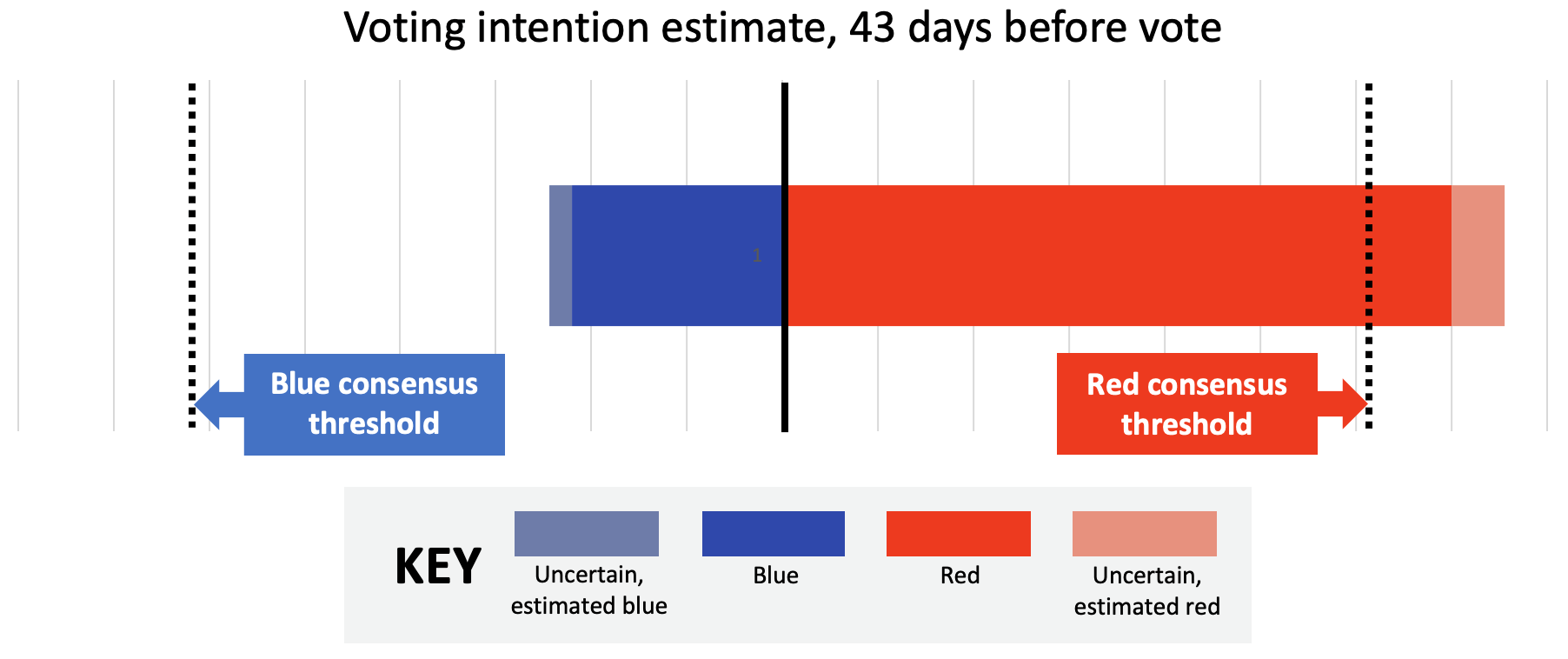

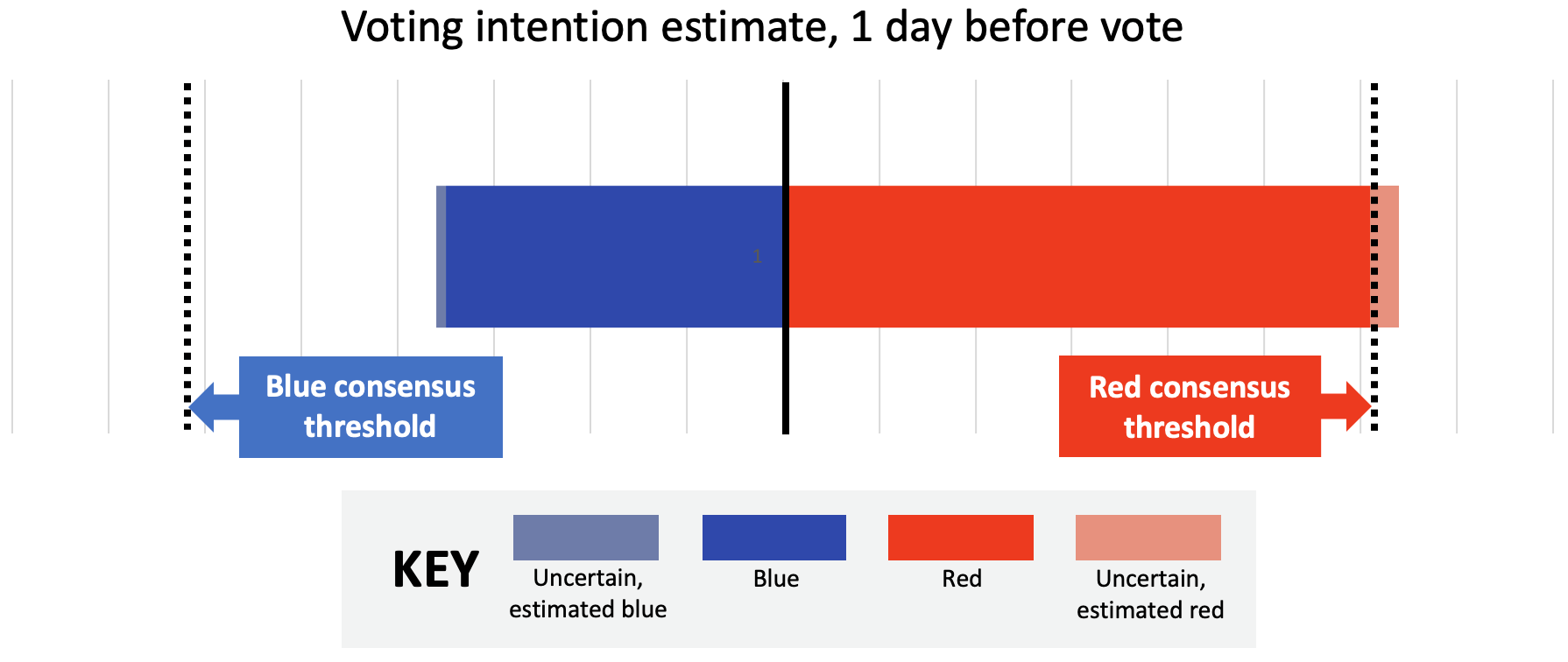

One way or another, progress was made, with both sides offering concessions in the days leading up to the deadline. With just one day to go, global consensus seemed to be converging at around 64%, albeit with an error margin of roughly ± 2%.

Final Problems

A few patterns of behaviour complicated the attempt to converge on consensus through negotiation.

Several independent studies had found that people with a voting intention of red were 57% more inclined to change their vote if they thought it would help consensus, compared to those with a voting intention of blue. Consequently, there were some calls to alter the global consensus to blue, as this could be more easily achieved. While this failed to catch on, some ongoing surveys did show an increased rate of switching in this direction, possibly by individuals hoping to signal their willingness to change should they be called upon to do so.

Relatedly, subconscious bias studies suggested that as many as 4% of people were lying about their intended vote. The lead hypotheses were that red voters might pretend to be blue to spur greater consensus efforts/negotiation; particularly committed blue voters (especially those subscribing to the Moderate and Anti-Consensus theories) might report red to reduce those efforts.

Subconscious bias studies were also used to assess the likely voting behaviour of those declaring themselves unsure, but these were unfortunately not representative. These studies were often conducted on student populations, or in countries where most of the ‘unsure’ were natural consensus/red voters who were choosing to be cautious and await greater certainty ahead of the vote. In contrast, the unsure population globally were largely places where consensus communication was simply poorer. These people were much more likely to choose blue than red, simply because blue was in general a preferred colour among most human populations. As such, estimates of how the unsure would vote were too optimistic.

Finally, both the Quiet and the Undecided undertook clandestine activity to try to tip the balance. Various methods were deployed to try to encourage citizens of the Undecided to vote red (e.g. airborne leaflet drops, social media sock-puppets, illegal radio broadcasts). Meanwhile the major organisations running the surveys among the Quiet saw attacks of many kinds: data-theft (primarily by phishing), but also tampering with stored data, undermining their ability to report survey results correctly. Some organisations detected these attacks and began counter-measures, with decoy data-sets and only a trusted few knowing which could truly be relied on. In the last days of negotiation, some of those trusted few fell mysteriously ill. These effects led both sides to reach inaccurate conclusions on the level of consensus in the crucial final days of negotiation.

On the last day, negotiations finally closed at an estimated consensus of 63.5%.

Results

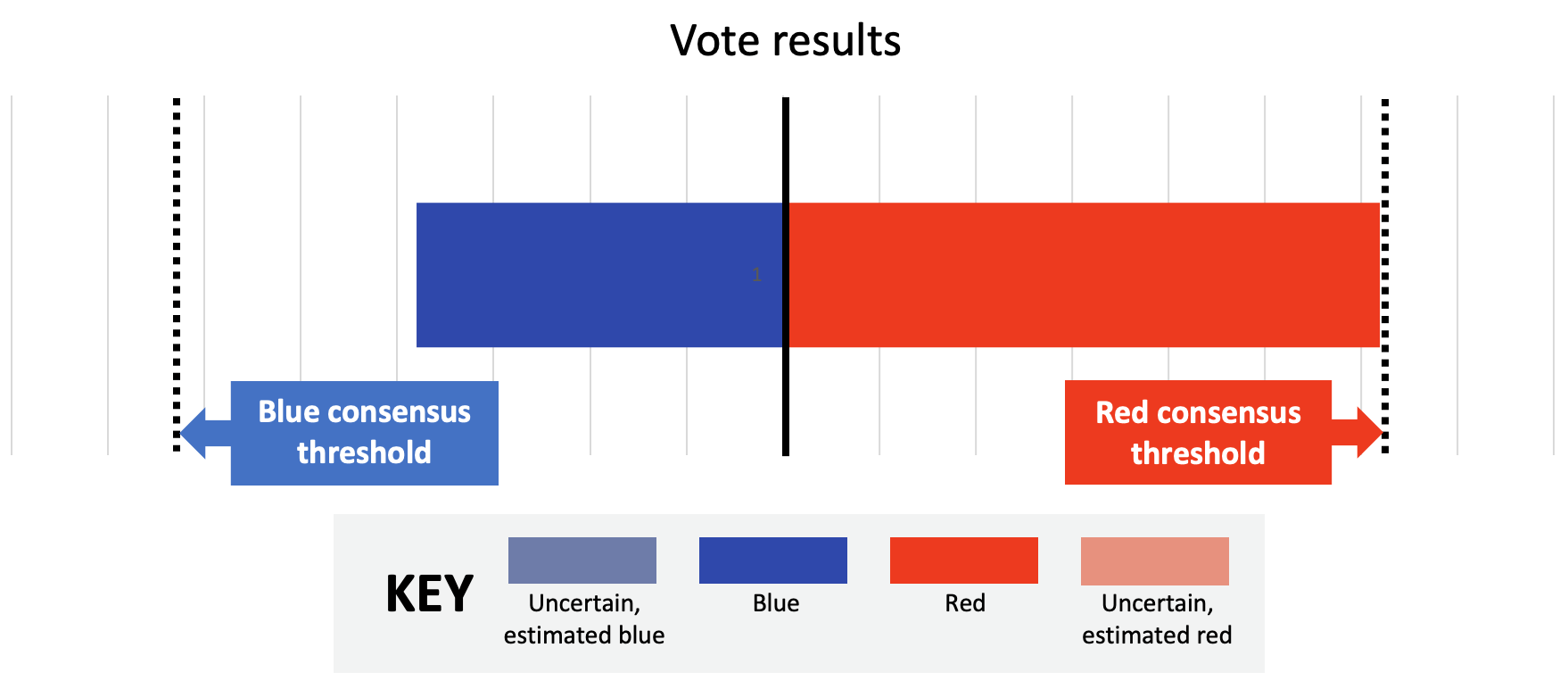

The vote was conducted in the normal manner, using the same approach as the message. The final tally was 61.8% red, 38.2% blue.

The consensus threshold of 62% was not achieved.

Following our usual protocol, all human memories and all digital and physical evidence of the prior 64 days have been overwritten with our baseline forecast of natural events for the time period.

In the highly unlikely event of humans attaining Type III habitat expansion, a revisit should proceed as standard. Otherwise, we do not see any grounds to recommend a reduction to the standard revisit period of 212 solar cycles.

- Report ends.

Tim Mannveille tweets as @metatim and doesn’t often write things like this, but you might appreciate Paradoxic Fandom. Thanks to Josie, Matt P, Ben H and Ian H from Hutch for their feedback on this story.