If you’ve somehow found yourself looking at this page but actually want to avoid Spoilers for Inception, you should leave now.

Right.

People are posting Inception Theories all over the internet, but even the ones that agree with me aren’t explaining it properly. So naturally I’m here to try to put that right.

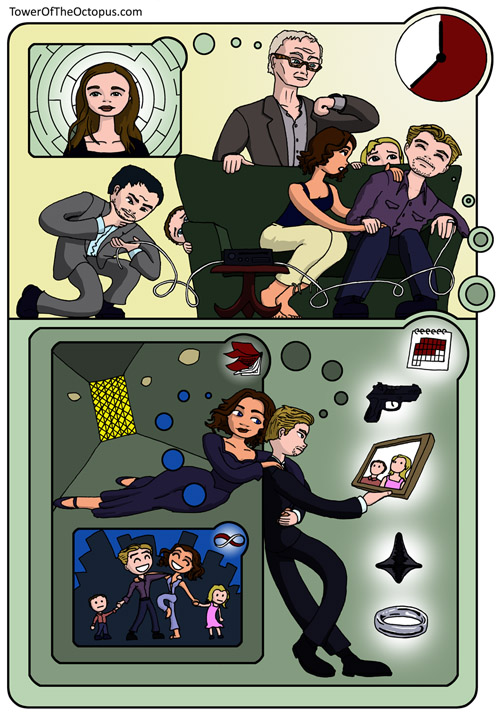

Of the major categories of theories out there, my preferred interpretation of the film is this: Mal Was Right. More specifically, at Mal’s external direction, Saito incepts Cobb to believe he must wake up, and Ariadne purges him of his demons. Here’s a diagram that shows what I think the underlying setup actually is (click for full size):

I’ll first explain what’s happening in that diagram, and then explain as briefly as possible why I think that’s the case, closely referencing lines in the film at each point.

The Diagram

Prior to the moment shown here, the flashbacks seen in the film took place. Mal (Marion Cotillard) and Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) went into limbo, Cobb incepted Mal so she would want to wake up, which she did first by joining Cobb on the train tracks in limbo and then by jumping from the building after failing to convince Cobb they were still dreaming. She thus reaches the top level of the diagram.

Cobb remains in a nested dream. In that level, he believes Mal is dead, blames himself, and although he wants to get back to his kids he’s punishing himself for what happened. At the same time, he is haunted by his subconscious projection of the pre-incepted Mal, who just wants him to hang out with her in limbo forever.

At the top level, Mal realises that Cobb is effectively in danger, as he could potentially be drawn back into limbo and lose his mind. She calls Miles (Michael Caine) for help; Miles brings Saito (Ken Watanabe) and also realises the character we know as Ariadne (Ellen Page) might be able to help. They formulate a plan to incept Cobb so that he will wake up.

The Reasoning

When interpreting a film like Inception, a good guideline is to try to take as much of the film as possible at face value. The more of it it you treat as being a misrepresentation, the more interpretations become possible, and things quickly get out of hand.

The following is based on notes I took while watching the film for a second time, so while the dialogue may not be word-perfect the sequence of events and key lines are accurate.

The Setup

The first scene to note is in the helicopter, when Saito requests that Cobb perform an inception. Cobb asks for a guarantee, but Saito has no way to prove he can and will arrange for Cobb to go home. His final plea to Cobb is interesting:

Saito: Do you want to take a leap of faith, or become an old man, filled with regret, waiting to die alone?

Cobb seems to be moved by this, and ultimately agrees.

The next scene to note is when Cobb visits Miles, where the following exchange takes place:

Miles: Come back to reality Cobb… please.

Cobb: This last job, that’s how I get there.

That’s top-level Miles, creating the subconsious idea that after this job, Cobb can come back to ‘reality’.

Miles then arranges for Ariadne to join the team. As they begin to train her, Ariadne investigates Cobb. At one point he is connected to the dream machine alone and she joins him, to discover that he is attempting to lock away the projection of Mal, but evidently can’t resist going back to her. She presses upon him the idea that this won’t be enough:

Ariadne: You’re trying to keep her alive, aren’t you? You can’t just create a prison of memories to hold her in. Do you really think that could contain her?

Once the inception begins, Saito is shot, and it is explained that under their heavy sedation death will put you into limbo, where time passes much faster and you can effectively lose your mind. At this point there is a reprise of the earlier dialogue as Cobb expresses concern that Saito will fall into limbo and forget their arrangement, but Saito reassures him:

Saito: I will still honour our arrangement

Cobb: No, you will be an old man

Saito: Filled with regret…

Cobb (seemingly unsure of why he is saying this): … waiting to die alone.

Saito: No, I will come back, and we will be young men again.

The Missing Scene

Later, Ariadne pushes Cobb for more detail on what happened in the past, and we are given a more detailed flashback. He explains how he planted the idea that they were not awake, and this idea remained with her even after they both escaped limbo by lying on the train tracks.

Mal is seen at a chopping board, toying idly with the spinning top in her left hand. At this point, one particular scene is conspicuous by its absence. We know Mal uses the top to determine if she is still in a dream. The natural thing to do would be to spin the top, but we are not shown this happening.

We can infer what must have happened. If the top had kept spinning, Cobb would have been forced to admit she was right; therefore, it must have stopped. Why was this not enough to convince her? The clue is in this piece of dialogue:

Cobb: If this is a dream, why can’t I change anything?

Mal: Because you don’t know you’re dreaming.

Mal’s hypothesis would appear to be that as the dreamer, Cobb shapes the world to his own assumptions – he doesn’t think he can change anything, so nothing changes; he doesn’t believe they’re dreaming, so the top falls. (This idea is also endorsed by Saito’s line from near the beginning: “In my dream we play by my rules.”)

While this might seem a bit of a reach, we can also infer that the use of totems, invented by Mal, changed after this point. It instead became about the heft of the object, and rules about others touching the object were introduced. Cobb learned from the mistake of using the top.

(We might also ask why such a scene wasn’t shown. My guess is that showing Mal make this argument in any more detail would lend too much weight to the “It’s a dream” interpretation at the end; it would also risk alienating the audience seeing it for the first time, for whom the top is a key navigational aid).

The Final Setup

Finally in the flashback we see Mal’s apparent suicide, where she asks Cobb to make a leap of faith. Now we understand something strange is happening – Saito echoed this line in the helicopter, then associated with it the risk of becoming an old man, filled with regret, waiting to die alone.

If Mal was right, and her suicide woke her up, then the situation depicted in the diagram arises. The best way for her to get Cobb to wake up is to incept him, just as he did to her. But this would be difficult, because he knows how it is done. We’re also told the mark for an inception must believe they came up with the idea themself. As we’ll see, this is exactly what happens.

At the close of this interlude, Ariadne lays out exactly what Cobb has to do in order to move on:

Ariadne: Your guilt is what powers her. If we are to succeed you have to forgive yourself, and confront her

After the apparent failure at the snow fortress, it’s Ariadne who proposes they enter limbo to bring back Fischer. There they confront Cobb’s projection of Mal. Guided by what Ariadne has said earlier, and helped by Ariadne in the moment, Cobb finally rejects her:

Mal: We can still be together… right here.

Ariadne: You can’t stay here to be with her!

Cobb: I’m not. […] I can’t stay with her any more because she doesn’t exist.

The Inception

Ariadne and Fischer kick out of limbo, leaving Cobb to bring back Saito in a climactic scene given special emphasis by being introduced at the very start of the movie. Here, the inception takes place: Cobb echoes the lines he has been primed with, convinced that it is his own idea that he and Saito are not really awake, while actually delivering exactly the message the real Mal wants him to receive (full dialogue taken from IMDb):

Saito: So have you come to kill me? I’ve been waiting for someone to come for me…

Cobb: Someone from a half remembered dream…

Saito: Cobb? Impossible – He and I were young men together, now I’m an old man.

Cobb: Filled with regret…

Saito: Waiting to die alone…

Cobb: I’ve come back to remind you of something… something you once knew…

[the camera dwells on the still spinning top]

Cobb: that this world isn’t real…

Saito: To convince me to honor the arrangement.

Cobb: To take a leap of faith, yes. Come back, and we’ll be young men together again. Come back to me…

[Saito reaches for the gun]

Cobb: Come back…

As Cobb delivers these lines, he looks confused, as if he’s not sure where they are coming from. He has been incepted.

The plan as originally stated seems to be complete, and Cobb returns to his kids. He spins the top, but does not wait to see what happens to it. It’s apparent that at least the first result of his experience is that he is no longer concerned with which world he is in; having forgiven himself and let go of his regrets, he allows himself this moment of happiness.

If the inception worked, it’s possible over time he will come to believe that Mal was right after all, ultimately committing suicide. On the other hand, thanks to Ariadne guiding him to reject the temptation of his projection of Mal, he’s no longer in danger of falling prey to limbo. As such, even if the inception doesn’t work, eventually enough time may pass that he will simply wake up when the dream comes to an end naturally.

Bonus Points

The idea built up in Cobb’s mind is that if he does not escape the dream, he will become an old man filled with regret. It’s interesting that the song chosen to signal the end of a dream is “Je ne regrette rien” / “I regret nothing”, associating waking up with having no regrets.

Even under a more straightforward interpretation of the film, Ariadne is very mysterious. Aside from having an obviously fitting name for someone that will lead Cobb out of the labyrinth, Cobb observes that he has “Never seen anyone pick [dream architecture] up so quickly”; she’s also aware of the plan while in the dream, despite the fact that Cobb later says to Fischer (possibly as misdirection) that to do so takes “years of training”. Her active part in investigating and then purging Cobb’s hangups is also particularly obvious on a second viewing.

Finally, a nice line which is by no means definitive, but still gives you pause if you’re thinking along these lines at the time you hear it:

Cobb (on the phone to his kids): Mommy’s not here any more.

Child: Where?